Editor’s Note: The What, Why, and WTF is a fortnightly article series that explores the culturally pervasive elements of gaming, those parts of video games that seem to have left some mark on gaming as a whole or Nick just finds really interesting. It is in no way an academic source, despite liking to pretend it is.

Mirror, mirror, on the wall, why are cutscenes so banal? I just can’t see why they’re great, when all they do is irritate; They appear in every triple A, dazzling senses with displays; While I sit still in my chair, remembering that I breathe in air; When all I want is to engage, cutscenes serve to fuel my rage. A game, you see, is like a rhyme, which cutscenes destroy by shoving completely superfluous nonsense that you have no way of interacting with beyond watching your character do cool things… Over time! Yet there are games with them that I adore, Metal Gear and Silent Hill are examples that I go for; And now this rhyming is getting tedious, so let’s start getting a bit more serious.

So, I don’t hate cutscenes that much, but I’ve never been a massive fan of them. From a game design point of view, they disrupt gameplay, and that’s bad, right? The last thing I want to happen is to be dragged out of my gaming zone to watch a clip about the main character’s girlfriend… So then why do I love Metal Gear Solid so freakin’ much? The whole thing is cutscene after cutscene, sometimes only being allowed to take a few steps before another one hits, but I love it. Normally, cutscenes enrage me, but then something like that comes along, and I forget that I ever had a problem with them. Then there’s QTE’s, but, look, let’s just nail down what it is about cutscenes that makes me love and hate them so ambiguously.

The term ‘cutscene’ has always been a fluffy way of describing sections of a game that a player has little or no control over, like an in-game movie or QTE. There’s not one strict method or technique that is a cutscene, but they’re usually used to drive the narrative or break up segments of gameplay by limiting player interaction. The problem, as I’m sure you already know, is that limiting player interaction is not something you want to happen all that often. You’ll be leaning up so close to the TV that your eyes feel like lightbulbs because you’re that immersed in the game when, like a Creeper standing behind you in your underground Minecraft fortress, a cutscene invades your screen. It’s not intolerable, but it ain’t exactly pleasing, and it’s worse when it’s unskippable.

You can’t skip past HOW AWESOME I AM LOOK AT ME PLEASE LIKE ME.

The variety of cutscenes and their frequency of use in the game can drastically affect a player’s enjoyment of that game, not to mention the quality of the cutscenes themselves. Let’s take Metal Gear Solid and Metal Gear Rising as examples, because Metal Gear is pretty renowned for it’s legendary cutscenes. MGS’s cutscenes are lengthy, but it’s a fairly slow-paced, story-driven game with variably long chunks of gameplay in between them, and the ideas on show could never be fully explored as well as they are through the cutscenes (even if they are conspiracy-levels of insane). They encourage you to think and engage with the game beyond mashing your thumbs into a controller for a high score, and let’s not forget Kojima’s mastery of cinematography.

On the flip side, MGR’s cutscenes were as frustrating as eating a live alligator. The game was a helluva lot faster, had a lot more cutscenes briefly interrupting the game’s flow, and were used to prove that Raiden is 100% cool without making him any cooler than a used band-aid. The helicopter scene in particular left me wondering why I couldn’t have done it in-game; it’s not like I hadn’t done crazier things before that point, so why restrict me from doing it!? They became an exercise in tedium despite being under 5 minutes a piece, as opposed to MGS’s genuinely interesting cutscenes that could last over 20 minutes. It seemed counter-intuitive that the game that let me do things was worse than the one that I had to sit through movies to interact with. Why? It’s a delicate balance between what’s enjoyable to watch, what’s enjoyable to play, and how much of each is in the game.

Video games are, in essence, complex reward systems. If you complete a series of challenges, you get can points, a 1-UP, or even a cutscene. What this means is that cutscenes need to be rewards themselves to match the rewards system of the game. The nature of these rewards depends on the game (horror games’ rewards might not make you smile), but the cutscene itself must be satisfying within the context of the game. If it feels superfluous or dull, then it’s not a reward, so why do I, the player, need to sit through it? There may be sections that will outright punish the player through a cutscene’s events (think MGS’s torture scenes), but they can still serve to advance the plot, which can be the best reward of them all if the plot’s good enough. However, too much usage of cutscenes and you’ll lose one of the best parts of video games: Flow.

That stop button? Flow killer.

You know that ‘zone’ you get into when you play, say, Tetris for hours without realising? It’s called flow, it’s a good state to be in, and it’s very closely related to the one-more-turn effect. Now, imagine if every 12 rows you removed prompted a short, skippable cutscene, a quick video from your boss congratulating you on your glorious victories for Arstotzka. You might be saying, “Aw, yeah, that doesn’t sound too bad,” but think it through. Could you tolerate cutscenes distracting you every 12 rows, or would you begin to ask why the cutscenes are stopping you from playing the damn game? While cutscenes can be used as rewards, when you play the game, you want to play a game. Incessant usage of cutscenes hinders flow, potentially stopping the player from immersing themselves in the game and entering that single-minded flow zone. This isn’t to say that cutscenes completely destroy immersion, but abusing them undoubtedly does. Finding a balance of gameplay and cutscenes depends heavily on the game, especially considering that the player could be doing what is happening during one themselves.

One of the benefits of using cutscenes is that events portrayed in them can transcend what the player is capable of in-game, but this can be a double-edged sword. While a cutscene involving a simple conversation about HDPE bottles between two parties might have players frothing at the mouth with rage at how they couldn’t do it themselves (I’d totally play Bottle Conversation Simulator 2014), watching your avatar single-handedly take down a helicopter might stir up a bit of envy in you. No one likes being reminded that they won’t be able to do certain things, nor is it enjoyable to be teased potential gameplay, but if the cutscene portrays actions that would be pointless or unrealisable within the game’s mechanics, then perhaps it’s an appropriate choice. This all gets a bit blurry when we start talking about QTE’s, and it gets even blurrier when QTE’s comprise whole games.

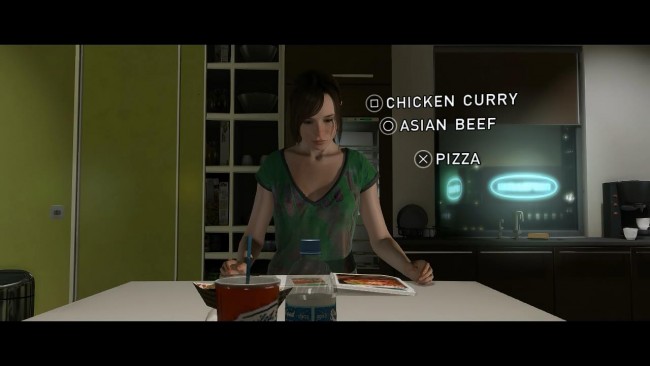

Cutscenes are no longer the humble sit-back-and-watch experience they once were. QTE’s made them interactive and have blurred the line between game and movie, for better or for worse. On the one hand, entire games are being made through QTE’s (like Beyond: Two Souls, Asura’s Wrath) or employing them heavily (a la God of War, Uncharted) to keep players engaged in almost exclusively story-driven experiences. While the idea of a six-hour movie might not sound appealing, a six-hour game is practically nothing, so utilising techniques from video games allows for grander stories to be explored without the risk of losing the player’s interest. On the other hand, interactive movies are still movies, and, last I checked, movies don’t tend to give me much control.

No ‘People’ option. mfw.

One of the strengths of games is the ability to offer a player agency, rewarding or punishing depending on how they make use of that freedom. Movies don’t tend to offer that kind of experience, and this limitation is evident in QTE-heavy games. While presented with choices, the options available to you will always be limited to what two or three pre-rendered sequences a director thought would be badass. Sure, Skyrim presents you with choices, but you can also completely ignore them and go kill vampires instead; you are given the agency to do that since the game’s mechanics are not built around pressing buttons at timed intervals to not die. Regular cutscenes might not offer QTE levels of interactivity, but they don’t tend to feel as tacked on either.

The main problem with QTE’s is the simplicity of interaction. To master a QTE is fairly easy: you hit a button at the right time. You get a minor payoff, and the game holds your attention that little bit longer. To master the gameplay of, say, Metal Gear Solid 4 takes a lot more effort but will provide more satisfaction in the process and (assuming no one rage quits) pique the player’s interest in getting better. While the QTE gets the job done, compared to the rich depth and variety normal gameplay offers, it can feel like a cop out when a QTE is used over the game’s mechanics to produce gameplay. However, in much the same way that cutscenes can be implemented amazingly in games, QTE’s have the same potential, and everyone who’s experienced RE4’s knife fight knows exactly what to cite as an example.

Anything involving this badass is also acceptable.

I might not be the biggest fan of them, but I can appreciate the cutscene’s place in games. When used correctly, they can elevate the game to stratospheric levels of memorability and emphasise the awesomeness of characters within a complex narrative. Their existence is a bit paradoxical, but QTE’s have helped bridge the divide between playing and not playing during a cutscene, which I feel much the same way as I do about cutscenes. I could still cite a million examples of awful cutscenes or QTE’s, but they’re still a valuable component to the medium of video games… Because Metal Gear Solid wouldn’t be same without them.