War is a not so fun topic to think about. People getting shot and killed for a cause that probably (and by that, I mean definitely) doesn’t justify murder isn’t pleasant. Video games gloss over these less than fun aspects because we don’t like to remind ourselves that we’re killing someone’s dad or sister. It seems counter-intuitive to design a game that confronts these depressing facts head on, but that’s what This War of Mine does. It’s a depressingly bleak and brilliant work that uses the medium for what it is, and that’s why it’s art.

If you’re unfamiliar with TWoM, it won’t be much of a shock to learn that it’s a 2-D survival game about war. You don’t play as a soldier or commander though; you play as a group of civilians in a war zone holed up in an abandoned house. During the day, you build improvements and try not to become suicidal, and at night, you scavenge for supplies in the debris of your old school or church. It’s hardly a ground-breaking game, but its perspective is what makes it stand out.

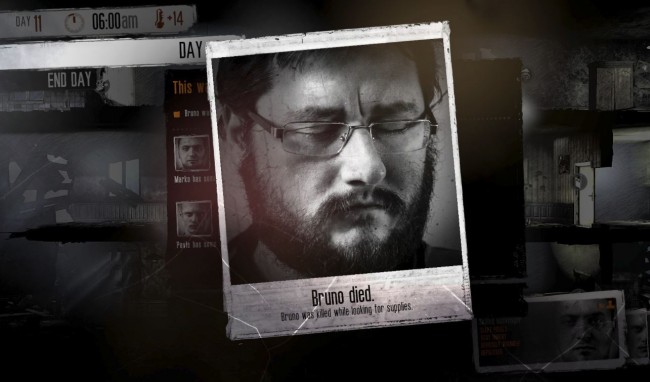

Instead of playing as Hunklord Powerhawk, you control everyday folk, like Phillip, a chef, or Marcus, an up and coming athlete. They have names, backstories and evolve as the game proceeds, and this is how the majority of the game’s narrative unfolds. The only explicit storytelling in the game is via updating character bios and a radio, and these are heavily dependent on the course your game takes.

The majority of the narrative is portrayed through actions done to or by the player, and this creates are far more powerful and unique emotional response than a cutscene or QTE. Killing a homeless man and sending everyone in the group into a spiraling depression will make you, the player, feel worse than just watching it happen. The horrors of war are not forced down your throat by a pompous narrator but are instead integrated into the mechanics themselves.

The effects of war in TWoM range from getting hurt to becoming depressed, but nothing is ever just a label. Depression has mechanical significance, changing the way someone behaves and possibly leading to them becoming suicidal. Instead of simply telling you that someone feels a bit down, you can feel the toll that the war has on these people through the game’s mechanics. This makes the bleakness of the situation more gripping than slapping a sticker on someone and saying they’re messed up. The game aims for an emotional response almost solely through the system that the game offers, and this is why it’s a bigger triumph artistically than, say, Valiant Hearts.

Half the problem with a lot of ‘artsy’ video games is that they’re not utilising the medium they’re apparently made for. Valiant Hearts was certainly okay, but it doesn’t come close to being art in my opinion. Games offer a chance for player agency and exploration, but Valiant Hearts felt more like a carrot on a stick with a striking visual style. Whoever you were controlling had to complete tasks in an extremely linear fashion, so it felt more like you were being dragged along than actively playing a game. The player was given a goal, but there was only ever one strict solution to achieve that goal, entirely neglecting the power of the medium. While this design might be fine for games that require a high degree of skill (I’m looking at you, Mega Man), Valiant Hearts felt like squandered potential.

Meanwhile, TWoM offers the player choice while simultaneously delivering a more potent message. The design of the game allows players to exercise their agency and explore various areas, and if you should run into trouble, too bad, this is war. There’s no grandiose storyline, no dramatic death scenes and no consolation for when you’re struggling; it’s just you and your decisions in this hell. When something happens, it cuts deeper than Valiant Hearts because you are the one who chose to do it, not because you were guided and forced into it. It takes advantage of the medium’s strength, and that’s something you don’t see often enough.

It can sometimes feel like a lot of games follow the carrot on the stick approach. They provide an experience, but it’s a heavily crafted, purposefully limited one, and it’s perfectly understandable why this happens. Game designers know better than anyone that players won’t go where you want them to unless you shoehorn them. Players will experience what developers want in an intended order if and only if you force them to, but this is self-defeating for a video game. A movie is designed to be viewed in a specific way (start to finish), TV shows are intended to be watched in consecutive episodes, but video games can’t function in this way.

By their interactive nature, video games cannot be presented and experienced the same way every time. They are not viewed so much as they are handled and dissected, and different people will approach and rip apart a game in different ways. Games like Tetris, Sim City, Dark Souls and Fallout understand this and disregard the idea of pre-defined experiences entirely. These games simply give you a set of circumstances, rules and then leave you to your volition to overcome whatever challenge should arise. Utilising what other mediums cannot provide is integral to art through design, and This War of Mine, while not quite as open as those examples, embraces this design mentality.

While extremely limited (because, you know, war), This War of Mine offers a design that encourages player exploration and experimentation. You are not told to build anything or go to a specific location; you have to weigh up the risks yourself and discover the consequences. The game’s narrative feeds into this design and vice versa since the people you control are not faceless avatars and react to your actions. The important thing here is that the design is simply a conduit for the player to exert their will and not just a series of tasks. TWoM offers a system that gives the player agency to elicit an emotional response through play, and this is art through design.

Video game design is more like architecture than script writing, and their interpretation as an art form reflects this. Imagine walking into a room designed by someone to make you feel sad when you start exploring it. That’s Gone Home. Imagine being inside a building where a door opens every couple hours to let you grab some food for a starving animal, except you need to hurt someone to get the food you need. That’s This War of Mine. The design brilliantly prods the often neglected part of your brain that deals with empathy and not wanting to kill people. Because of this, I’d consider it a triumph of video game art, and this gives me hope for the future.

The obvious sentiment of TWoM is that the human will to survive strong, even in war, but that’s not what gives me hope. It’s a game that tackles subject matter in a raw and genuine way, and it doesn’t suck. It does so by using the medium in a way that couldn’t express its message through any other. This game wouldn’t be a good movie because the interactivity is such a core part of the experience. Seeing something like this come out gives me hope that more games like it will emerge, ones that don’t rely on traditional forms of storytelling to convey a narrative about a serious topic.

Tackling the topic of war through a video game is a paradoxical task, but This War of Mine handles it brilliantly. It uses the interactivity of the medium to its advantage and creates a compelling experience without relying on ‘press X to feel’ sequences. This, to me, is what elevates a video game to becoming a work of art, which I’d most definitely classify TWoM as. War isn’t fun, and neither is TWoM, but it gives me hope for what’s to come.