Creating a game using an already well-established story is just asking for trouble unless you get it right. However, when Cyanide Studio started working on Call of Cthulhu, I was super excited nonetheless as I’ve been a Lovecraft fan forever. I eagerly began stalking for updates, read every rumour or titbit I could find, and felt like a creep standing over the developer’s shoulders with a scowl, waiting for this staple story for Lovecraftians everywhere to be ruined. I got so wrapped up being inpatient and pushing down the growing excitement that when I finally got a copy to sit and play I remembered something essential: I’d agreed to play a survival horror game.

In case being an awkward teen with a literary obsession wasn’t you, don’t worry, you can play and enjoy the game without knowing anything. Edward Pierce is a war veteran working as a private investigator, he has some issues and a haunted past, with a no less haunted future slowly building up around him. When he accepts a job involving a deadly house fire and some genuinely creepy artwork, it feels like one of those critical moments you could look back on when you wonder where it all went wrong. It doesn’t help that Edward has a drinking problem you can choose to indulge or ignore (it affects the story), but what is most worrying is that the island he leaves for is called Darkwater.

Call of Cthulhu opens with an ominous message, which made me squirm a bit as I remembered how dark and unsettling Lovecraft can be. I thought the game might ease me into it, ha! Nope! There was blood and gore everywhere, noises that made me insist my dog stayed in the room with me, and an overpowering sense of dread. There wasn’t much in the way of direction needed, as when has anyone ever opened their eyes in a room of guts and terrifying noises and thought “clearly, I should stay put.” Even under the intense pressure of the situation, I was pleased to see the standard of art and design was excellent and detailed, and even the mood lighting. This set the scene for the entire game, and that gloomy, horror-stricken cloud never left.

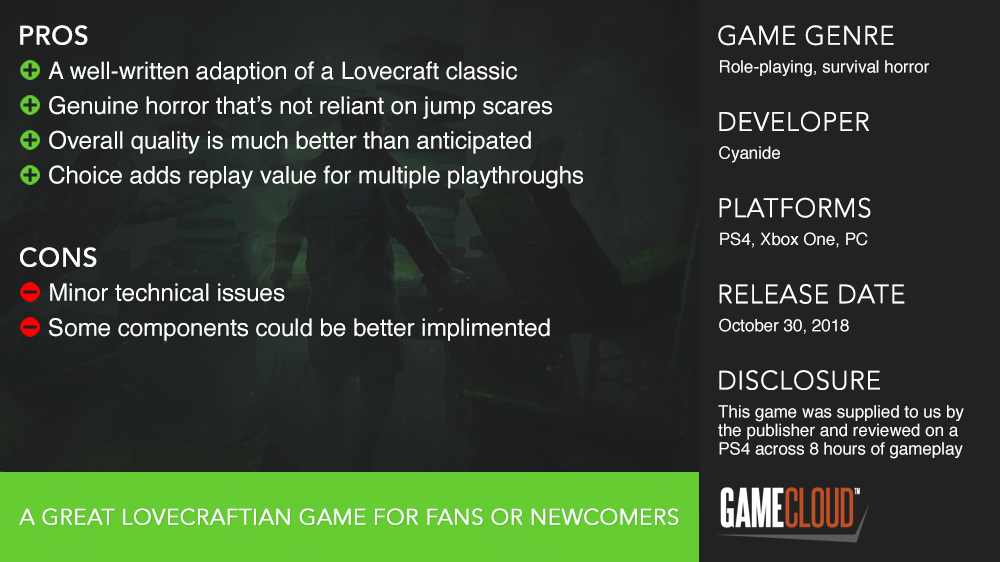

It wasn’t until leaving the prologue scene that I encountered my first less than brilliant factor, which is the difference between the cutscenes and interactive play. There is a notable quality difference in the animation, but more importantly, the dialogue volume is so loud in-game that I had to mess with the volume continually throughout my playthrough. The next issue I came across doesn’t seem to be widespread, but as it impacted my game, I’m still going to mention the load times. The pause between chapters is long enough almost every time that I felt it was damaging to the flow of the story. It only occurs the first time each chapter is loads, but still, it feels like waiting for dial-up internet.

In spite of that, however, the chapter breaks are also a positive point in the game, as the marked progress points feel like a counter, as you grow ever-closer to insanity or solving the Darkwater mysteries. The little recaps on the chapter screens are accompanied by a whole slew of pause screens extras – an invaluable guide in both detective games and iconic mythos. The level of detail in the case files, interactive objects to examine, and data on everything helpful or malicious discovered in each chapter also gives the game a landscape of information to get lost in and is a great way to pay homage to Lovecraft.

Fundamentally, the controls are logical and adjustable, the character points and upgrade screens are thorough and transparent, and even the compilation of your growing insanity is easy to use and access. As with every game that offers conversation choices that affect the game later, the options and use are entirely straightforward; although, I still managed to misunderstand and make some dense decisions. This is where I found that once your choice was made, that was it, and I love that about the game. If I could have kept saving and creating a different choice I would have had 27 save files and been skimming back and forwards between them to get the “best” outcome.

While upgrades are easy to manage, their in-game impact isn’t very clear. A perfect example of this was when I put the least amount of points in strength; I reasoned that if I had to find an entrance at some point, and it was relative to the story, then my physical strength wouldn’t matter, plus my other high skills would create ways of steering the conversations in my favour. The problem, however, is in this game, if you miss any hidden items, they are gone, and there isn’t a record to let you know what you missed. As such, I was careful not to miss anything, and this is where my character points caused a problem. I found three items that when put together and fastened in the right spot created a crank handle, and it said to try my strength and turn it. Now, logic tells me that if I’m too weak, I cannot set the handle, but I should be able to come back once I’ve got more strength and succeed. Nope. I tried, failed the strength test, and broke it, sending the handle flying with no chance to retry.

While Call of Cthulhu suffers from some minor technical issues, and a few things could be better explained, this never impeded my ability to enjoy the game. With different choices, better ways to use my skill points, and the possibility that the terrifying survival level wouldn’t take me seven tries again, it could be just as entertaining a second time. It was scary enough that I fought not to have a panic attack alongside Edward every time we hid, well written so that even with so much previous knowledge of the universe I could enjoy the narrative, and was simply a joy to explore overall. Cyanide did justice to both the pen and paper RPG Call of Cthulhu is based on and H.P. Lovecraft.