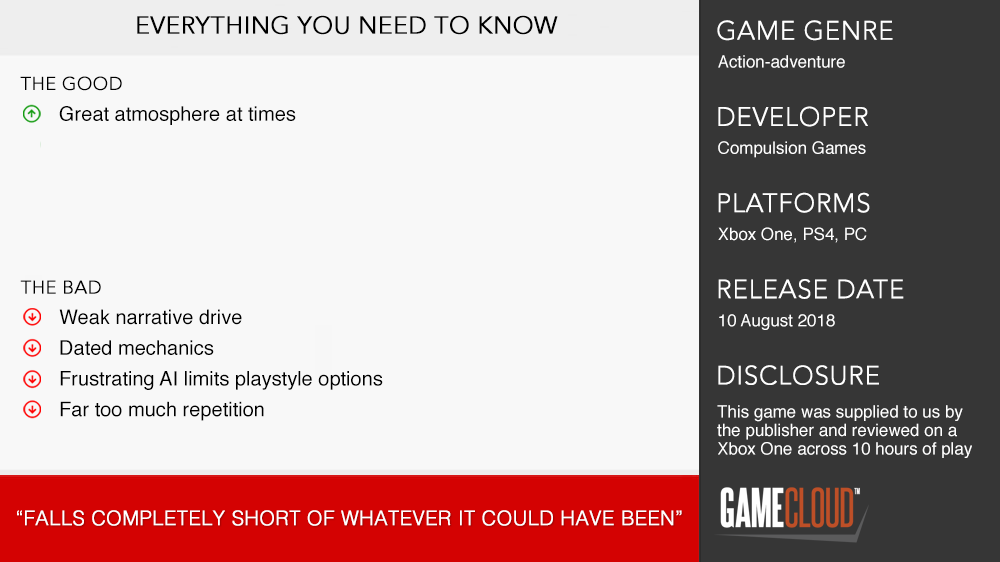

We Happy Few has been hanging just out of reach but not forgotten for years now, starting out with a successful Kickstarter in 2015, before being picked up by Microsoft and making a big splash at E3 2016. Compulsion Games even made a move you might expect from a larger, more experienced studio and held off releasing the game after receiving mixed feedback during last year’s Early Access to make sure they were only going to send out the best they could. In turn, I went in expecting a well-written narrative in the vein of a dystopian nightmare, a high-stakes survival game with a constant sense of paranoia, and an overall experience that was not only worth the wait but a reminder of the great work that can come from a small studio with big ideas. What I forced myself to play, however, was not that.

At first glance, We Happy Few appears to be a gaming experience of the red pill phenomenon; taking the red pill refers to waking up, no longer being sheeple and realising the “truths” of the world. A game like this could either be sincere and intriguing, or tongue in cheek, poking fun at the keyboard warriors and conspiracy theorists who live for that kind of thing. I was pleased to find that its themes tried to go deeper than that, focusing more on society today and our need to fit in and appear to be doing well and in control. The issue, however, is that the game inadverantly seems to fall into the cracks somewhere between being honest, and a silly conspiracy with very little weight.

To be fair, I liked the art direction and overall style of the game, even though at the end of the first hour it didn’t seem like there was much else to see as far as new areas were concerned. The lanky, almost rubbery looking people with their V for Vendetta faces were most definitely on the creepy side, whether they wanted to kill you or not. The late ’60s setting was also evident in some of the more delicate details inside homes when you could explore, though that wasn’t very often. Considering the hefty sneak or rogue aspect to the game, it was really disappointing only to find that most of the scenery was just that: buildings and doors that were just there to fill space. The contrast between the drug-induced, coming down and drug-free state were too understated, as well: they had the chance to be psychedelic every time you had to take Joy, but instead, everything just had a glow to it, and that was about it. The fact that the game is apparently trying to pass the message that Joy should only be taken as a necessary evil, the trippy times should have been beautiful and harder to pass up.

We Happy Few may look somewhat like Bioshock with aspects of Fallout, but it plays more like the first Fable game. It’s clunky, interactions had me frustrated at every turn, and your character’s sudden inability to leap a fence or use an item gave me a pitiful respawn stats. Basically, I didn’t enjoy any of the actual gameplay. In a survival game, you should be faster, quieter and agiler than most chasing you, and you need few skills to live. In an RPG you may require hundreds of items to carry with you, store, trade or craft with, and in a rogue game it’s all about stealth, strategy and the tools you need. I think We Happy Few started out as one type of game but changed its mind so many times that it decided to throw in a mish-mash of all these components. Worse yet, it does this and doesn’t bother to tell players how to do anything. I’ve played more than enough games to skip tutorials on using your menu or quick slots, but the lack of information here was both inefficient and frustrating. Eight hours into the game and I still couldn’t craft half the items it seems I should’ve been able to because I must have missed an upgrade kit somewhere.

The levelling system is self-explanatory, unless you were wondering how to get better at anything. Want to earn skills to be a better lockpick? Don’t bother. Aside from the fact that everything is more often than not EMPTY, you are only given a set amount of points to spend during your playthrough. I levelled up a handful times before I just left my points to start stacking up and ignoring them. It made such a little difference to the experience that I could no longer be bothered reading the explanations and just avoided the screen. I put my first few points into health buffs because the AI and combat system caused me so much grief that I thought it must make a difference. It did not. Instead, I started playing the game in such a way that someone like me with no discernible sense of patience, hated it even more – I took to hiding in empty alleys instead of planning an escape or fight every time, and boringly enough, it worked. The issue was that if someone became hostile towards me, even if there was no one else in sight and no alarm went off, I would suddenly be swarmed by more freaks than I could survive. Sure, I could outrun them sometimes or try fighting and healing, but there was no winning strategy except to slink round quietly and not accidentally engage anyone lest their magical friends appear to smash your skull in.

The worst thing about We Happy Few is that out of pure frustration I stopped caring about the story early on, and from there it wasn’t long before I’d seen all I needed to see. This could’ve been a brilliant game – not just entertaining, but the right kind of scary that makes you feel paranoid and somehow unsettled the entire time. I actually really liked where it was going at first, too – conspiracies are great fun and can make for memorable gaming experiences, as can a well-made game that deals with issues of mental health and social commentary. I didn’t believe We Happy Few was ever going to be a Nineteen Eighty-Four, but it fell short of whatever it could’ve been, and that was so disappointing – so much so that now this review is done, I’m never playing it again, and that’s the happiest I’ve been about the game.