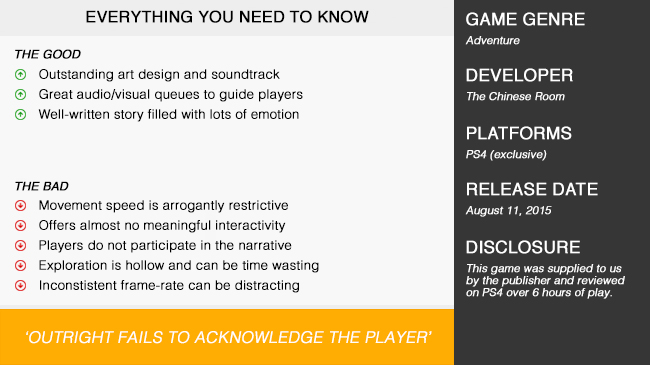

When I first played Dear Esther, it rocked my perception of interactive storytelling. I understood why some panned it for being a glorified ‘walking simulator,’ but I was too fixated on the big picture to let any criticism sully my appreciation for what the game was trying to achieve. I’m a firm believer that video games don’t need to emulate cinema to deliver compelling stories, so, for me, this experiment, while flawed, was the inception of gaming’s most progressive genre. But that was several years ago now, and since that time we’ve seen the foundation it laid evolve through titles such as Gone Home and The Vanishing of Ethan Carter. Admittedly, neither of the games got it right, but both took definitive steps forward to pave the way for The Chinese Room’s bold new take on the genre: Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture.

While touted as a spiritual successor to Dear Esther, there are no common links between the two titles. Set in 1984, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture takes place in a village in Shropshire during the apocalypse and tells the story of six different characters. The game takes place in an open-world where players are given complete freedom to explore the village and surrounding areas in whatever order they choose. There is only one objective to pursue, and that’s trying to work out what happened to everybody. Going in, I had almost no idea what to expect as I went on a media blackout months ago, and while I was instantly charmed by the lush art style and soundtrack, I quickly found myself growing frustrated with the core mechanics. The one and only connection I had with this world was walking, and it felt terrible.

It’s both tedious and immersion-breaking, and the undisclosed option to walk slightly faster by holding R2 isn’t much better. I’m sure there is an artistic justification for the pacing as it appears to be intentional, but I flat out disagree with forcing it on players with no alternative. It felt suffocating; so while part of me wanted to be in awe by my surroundings and the outstanding sound design, all I could think about was how uncomfortable it was to hold down R2 all the time. In fact, I didn’t enjoy my time with Rapture during those opening hours at all. It wasn’t just because the pace was slow either, it was because the world design produced the illusion that it was much more interactive than it actually was. I wasted too much time examining pointless set props when I could have simply soaked it all in and followed the light.

On that note, light is a recurring theme within Rapture as well as a design element I thought was well implemented. Basically, while you’re free to explore the game at your own accord, you’ll often encounter whirling balls of light that tie into the narrative and also point you toward unexplored points of interest. It’s a subtle way to ensure players won’t ever get stuck with no clue where to go, and it’s been integrated in a way that feels organic to the world. You’ll also be experiencing the story through various apparitions of light; scenes that are relived through ghostly-looking figures with audible dialogue. At first I was fascinated by the concept, but then I learned it’s all you do in the game. Explore empty scenery to watch visually hollow characters have disjointed conversations that don’t have any impact until much later.

Don’t get me wrong, the story itself is actually quite good. I’d even go as far as to say it’s well-written and emotionally engaging once it comes together. There is just little more to say as it works best when you know as little as possible. As an active participant, you’re basically nothing more than an observer whose in-game existence serves no purpose other than to create a non-linear channel for information and the illusion of interactivity. There is almost no meaningful interaction with the world and no genuine secrets to uncover. There is some basic environmental narrative to note, but without the ability to zoom in or pick anything up, it’s mostly hollow. There is no encouragement to explore other than to appreciate the scenery and locate the next in-game cutscene. That is the saddest story unraveling within Rapture.

What bothers me most is that The Chinese Room didn’t lift their heads to see what other games within the genre were doing; games they, themselves had inspired. A good story is simply not enough to justify a game, especially when it barely engages the medium it’s told through. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is practically the same game as Dear Esther, just done on a bigger scale with a larger variety of pretty environments. It’s not that it doesn’t have some good ideas, it’s that they’re not utilised to fit the interactive medium. Even the simple ability to pick things up would have helped, or, better yet, using the phones as a way to involve the player in the story with some two-way dialogue. The only genuine step forward taken in terms of game design are the visual and audio queues used to support the player.

Let’s at least stop to talk about how wonderful the game looks, and how incredible Jessica Curry’s latest soundtrack is. Rapture is so stunning in some regards that it hurts me to criticise it so harshly. Even if it suffers from a shockily inconsistent frame-rate that further amplifies the muddy controls on occasion. Not to poke fun, but as a ‘walking simulator,’ it’s probably one of the most visually captivating landscapes I’ve encountered; even if it’s devoid of all life other than the shifting weather patterns and passing of time. There are lots of unique, tiny details to pick up on, but, for me, the experience was really brought to life through Jessica’s dynamic sound design. I really appreciated how it captured the vibe of a world since abandoned but living on. Artistically, there’s so much that the team can be proud of.

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is a game with a compelling story to share; it’s just a shame that it doesn’t allow the player to be apart of it too. This comment is not intended as yet another jab at the ‘walking simulator’ joke, either; not when you consider walking to be one of the title’s biggest frustration points. In the past, I’ve spoken at large about the potential of interactive narrative games such as Dear Esther, and openly celebrated the progressive steps taken by those titles it inspired. Rapture is a wonderful audio/visual experience with some fascinating ideas, but The Chinese Room outright fails to acknowledge the player as anything more than a spectator and that’s not good enough. There’s no personal connection with the world, no meaningful exploration, and no reason for you to be there other than the game puts you there. I’m not saying it won’t be enjoyed, but it’s a step back from the definitive leap the genre needed.