“Papers, Please! Makes you feel awkward and uncomfortable emotions, before making you question if you were ever a good person.”

Zdravstvujtye, comrades! I’ve been playing “Papers, Please!” this past week, which at this point feels more like “Sophie’s Choice: The Game”, making the player work at the border control booth for what appears to be a dystopic, militant dictatorship named Arstotzka. After winning a lottery which has allowed your nameless character to work for 30-days as the lone border control booth operator, it is your job to determine who is eligible to enter the country, with the rules being changed on a daily basis by a controlling government. You will work to support your family with the pay that you receive each day, covering the basic necessities like food, rent, heat, and medicine, or buying upgrades for your work booth to make processing people easier. You dole out the cash, go to sleep, and then start the whole process again the next day, assuming that your family hasn’t died in the night. The gameplay design, like its artwork, is very minimalistic, creating complex memory puzzles from a single concept, and really shows that games aren’t just about mindlessly, and hilariously killing the bad guys. They’re also about filling you with self doubt and making you question what morality actually means.

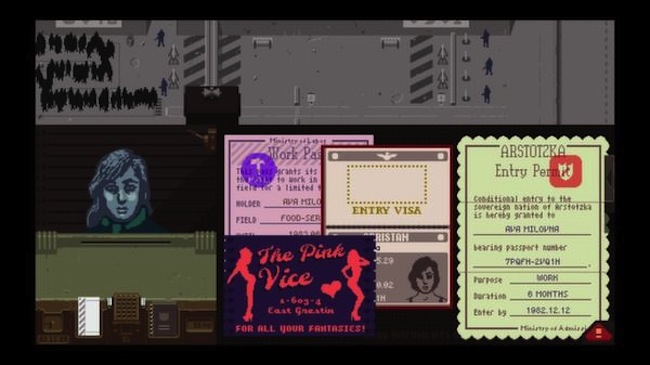

At the beginning of each day, you throw open your shutter and sound your speaker to call through the next entry candidate, demanding and then scrutinizing the documentation that they provide, and every applicant that you process is an extra five credits in pay. Having a little in-game reference book makes is handy at first, as you can check it at any time and the rules are pretty straightforward. Soon, however, the reference book becomes a necessity as checking requirements increase with complexity; the rules might be as simple as “Stop all foreigners and allow only nationals”, which can be confirmed with a quick glance at the distinctive passports. However, by the end of the game, you’ll need to check that they have all the required documents, identification and that they all correlate. Although, this is completely separate from the security measures that have to be taken, which can include checking fingerprints, scanning their bodies (nudity can be turned on/off in the game menu), verifying that each document hasn’t been forged, and detaining them for suspicious activity. It’s amazing that the game falls short of having you pull on a rubber glove, snapping it ominously as you tell the entry candidate to “pucker up”, because to me, it felt like that was the logical conclusion. However, the real crux of the game is not necessarily the things that you do, but rather the things that happen afterwards as a consequence.

The game pretty quickly highlights why these measures are so necessary, cutting one day short when someone climbs over the wall and hurls a bomb towards the city that kills the guard on the other side. There were at least two instances where I failed to spot someone with explosives on them, allowing them to slip past the guards on the other side and suicide bomb them into charred smears on the pavement. Not only does this cut the day short, meaning that I lost money because I didn’t get to process applicants for what was left of the day, but it means that I’m responsible for the deaths of the terrorist victims. Their blood is on my hands because I didn’t spend enough time checking their papers. The logical solution to this is to reject a persons applicant, but deciding the fate of the rejected candidates was somewhat uncomfortable to deal with throughout the game as well. It’s either returning them to where they came from or calling armed guards to haul them off, and It feels strange to be ordering the disappearance of a person since the game’s atmosphere suggests that they’re not coming back. Even sending them away can be distressing when they’re begging you not to, saying they’ll be killed if they go back to where they come from.

It’s worse when that uncomfortable feeling disappears, with fearful pleas and aggressive arrests becoming routine, leading to certain compromises that you may not have been willing to previously make. Mistakes are a near-inevitability which overtime will erode at your already small pay, but they can become easier to make too often as the caveats and addendum of checking papers stacks up, but there are ways of off-setting these set-backs. There are guards who will offer you a side bonus for detaining more people than you might otherwise; entry candidates will offer you bribes, sometimes fairly hefty, to illegally enter the country; a shady, revolutionary organisation will attempt to recruit you to their cause, having you betray your country for a huge reward; and intelligence agencies can look into you for dealing with shady, revolutionary organisations.. The different possibilities that pop up in-game are as numerous as they are varied, with your choices directly affect the outcome of the game, to the tune of twenty possible endings, all of which are dependent upon the fine balance that you strike between loyalty to your country and trying to keep your family alive. The endings definitely aren’t all happy, as was the case on my first play through when my entire family died overnight after the sixth day and the government fired me from my job for not promoting a healthy “family life” as part of their core values.

When I sleep at night, I can hear their voices whimpering in the cold. I’m not talking about in-game.

All of this decision making and money grabbing leads to the segment which takes place at the end of each day, and is arguably the most important part of the entire game: using your money to support your family. You have four family members who can all be ill, hungry, and cold, and it’s your job to earn the money to make sure that they’re fed, warm, and healthy. The flip side is that when you can’t make enough money during the day, you also have to decide who gets medicine, or if anyone is actually eating tonight. You can’t even see these characters, they’re words in bubbles that have status tags underneath; you can’t talk to them, you don’t hear anything from them, they are just there and your responsibility. In a way, it’s a great way of conveying the life of your character in an indirect fashion: You’re poor and over-worked, you don’t have the time between working and sleeping to actually spend time with your family, so the people that you come home to everyday are strangers that rely solely on you for their survival. Yet these characters and their plight have done more as faceless, voiceless entities to elicit an emotional response from me than even the most well written of RPGs, and the desperation I felt when I couldn’t afford to feed my family for the second day in a row genuinely felt like my own.

The game itself does not pull any punches and doesn’t even attempt to sugar coat the events which proliferate the story. It’s an attitude that mixes well with the disturbingly enjoyable setting of a country that sees that your family has just died and says, “Get out of job”. Papers Please is an independently developed title from creative mind of Lucas Pope, and is currently available on Windows & OSX via Steam or GOG. Honestly, it’s a game that makes you feel awkward and uncomfortable emotions, before making you question if you were ever a good person. If you’re into strange indie games that think outside the box, I absolutely recommend you check it out.