My first encounter with Fallout wasn’t with one of its games or a piece of related fiction. It was an online argument (perish the thought) about how a then-newly announced Fallout 3 was ripping off the recently released BioShock. This stemmed from the fact that Fallout had traditionally been a CRPG, and the third title in the series was shifting to being an FPS ARPG. Weirdly, however, this is far from the crux of what makes a Fallout game, well, a Fallout game. As I’ll convey in this meandering wall of reminiscence, the worth of a Fallout game lives and dies by player choice.

And yes, you will die by some of those choices.

Entering into the new console generation late, BioShock was one of the first games that I picked up with the Xbox 360. For the few that haven’t played it, the game takes place in a dilapidated, underwater utopia-turned-nightmarish-dystopia called Rapture. Everything that happens in the game is a mystery to be unravelled, thus its details don’t bear discussing here, but what drew me toward the city of Rapture most was the atmosphere. The city of Rapture is as much a character in BioShock as anyone with a speaking role, with just as much charm, allure, and hidden horror, ever-changing and developing throughout the game’s story. Most importantly, it nailed one of the central themes that Fallout is known for: picking through the debris of a fallen civilisation, so that you can survive the establishment of the next.

More than that, taking things that once had a determined purpose and then re-purposing them for this dangerous new world had its own appeal. Particularly when those items, or their aesthetic, hold for us in the real world diametrically opposed connotations to what we see them being used for on-screen. For BioShock, this would be things like the white-washed wholesomeness of a carnival vending machine being used to dispense addictive, gene-altering substances. As much as I loved BioShock, however, it felt too constricting. Something was missing for me. The story was fantastic, but once it was over that was it – the magic of the world faded, and you knew all there was to know. You didn’t guide the story, it guided you; to borrow a phrase from Andrew Ryan, “A man chooses, a slave obeys.”

And negligent heroes indirectly destroy everything they once held dear.

Following my time with BioShock, it was the internet shit-flinging going on around both it and Fallout 3 that first turned me onto the Fallout series. For the record, to those who sincerely thought at the time that Fallout 3 was ripping off BioShock – what was wrong with you? I picked up Fallout 3 on release, excited to play, and at least on my first attempt, I became disinterested. I had barely any idea of what I was doing, wasn’t building my character toward any particular play style, and nothing about the world seemed to grab me. Plus, and this is a very valid criticism of Fallout 3, it was visually dull. The world itself is a beautiful display of ruin and annihilation, hidden under a drab, uniformly green filter that makes everything look as awful as possible (and not in the “it’s supposed to look that bad” kind of way.)

It took me a few more returns to the game to really get into the swing of things, all the while consuming much in the way of post-apocalyptic media in-between. The Mad Max movies, World War Z and The Zombie Survival Guide, NCIS; fiction whose authors really tried to create an idea of a genuinely shitty world to live in, yet they still try to survive and find purpose. The first time I would finally play through to the end of a Fallout game was when I came back to Fallout 3 for what had to have been the seventh time with a fresh, new understanding: I could do whatever the hell I wanted. And that is the point of Fallout games, for the most part. Through the machinations of fate, your character has been placed at a pivotal moment in the series’ history, and you get to decide how it plays out.

Pivotal.

When viewed through that lens, suddenly you become so much more invested in the world and the freedom of choice is much more apparent. Those raiders causing trouble? They’re only doing so by your grace or negligence, and it’s up to you to decide how you feel about that. The outcome of a faction war over significant territory will be determined by your actions, through violence if you have to, or manipulation if you so desire. You can make a deal, double-cross your partner, and then screw over the person you made the second deal with to get even more of a payday. Why am I only giving examples of using this freedom for evil? Because in a virtual world, morality is already kind of iffy. In a virtual world where civilisation has disappeared, and you’re given the same tools as any other virtual world, morality becomes entirely relative. Relative, that is, to your current mood, and I was a hormonal teenager at this point.

Fallout 3 still had something of a “moral compass,” however, and would change your alignment based on the nature of your deeds. Thus, Fallout 3 was a pretty great indicator of how people might instinctually act when normal consequences for actions are taken away. When I first played Fallout 3, I would almost invariably end up becoming the Last, Best Hope of Humanity. I’d grown so accustomed to playing the hero that choosing the good option felt natural, and the writing of Fallout 3 was decent enough that I felt compelled to do so. This is, of course, until I remembered that being evil is also an available option.

“Why hello there, juvenile compulsions.”

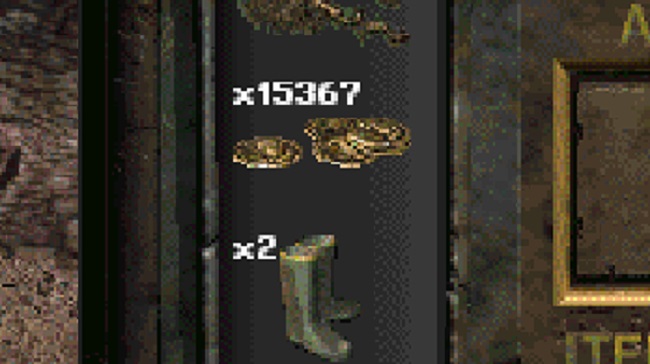

One of the first things I did in my “evil” playthrough of Fallout 3 was to agree with Lucas Simms to dismantle the nuke in the center of Megaton. I immediately went and spoke to Mr. Burke, making a deal to detonate the bomb instead – demanding half up-front, of course. I ratted Burke out to Lucas, let Burke kill Lucas, then killed Burke, and looted them both. Shortly thereafter, I went to Tenpenny Towers, blew up megaton and collected my reward, killed Tenpenny, then looted him too. All the while, instead of thinking about the moral implications, all I could think was: “GOSH this is fun.” I merrily murdered my way across the Wasteland and completely forgot all about dear old dad. Why bother with the main quest when there were caps and shenanigans to be had? Liam Neeson is overrated anyway.

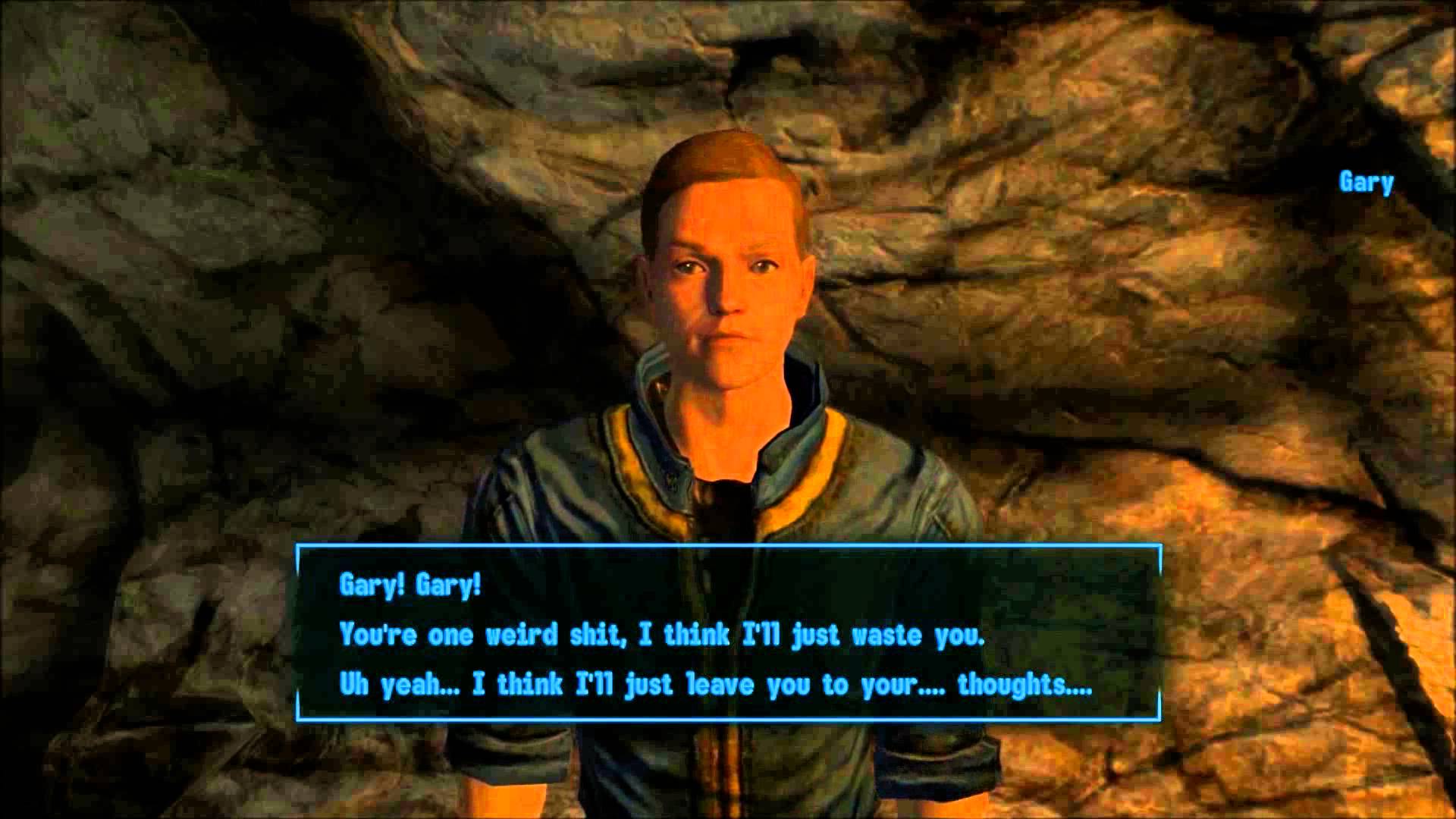

In Fallout 3, it was difficult to really feel the depth of those consequences, which can mainly be put down to a somewhat unambitious story and many side-quests that lacked detail. Fallout: New Vegas, however, is a different story. Literally, and a good one at that. Widely considered to be the best game in the series in terms of writing, and my personal favourite entry, New Vegas raised the series’ bar for immersion and laid bare the impact of player decisions. There are so many excellent, story-driven examples for why this is the case, but, for me, it was something completely banal(ish.) There’s a quest you can pick-up a-ways into New Vegas to organise the caravans and start a regular trade route. It’s highly beneficial, but I found that I couldn’t complete the quest. As it happens, I’d spent a good portion of the game luring caravaneers to their deaths and looting everything on them, which meant I’d killed most of the characters I was expected to negotiate with. That simple consequence made everything in New Vegas feel so real to me then.

Also much, much harder, and I should probably stop with the indiscriminate NPC murder.

New Vegas got its hooks in me so deep that, across three different platforms, that game has extracted at least 600 hours of my life from me. That’s not a typo or an exaggeration, nor even bragging of any kind, I just… I have serious problems with this series and self-control. That said, even the truly obsessed can grow bored of something given enough time, and so I went looking into the old games. To say that they’re technically janky by the standards of today would be setting a world record in understatement, but this problem can be overcome. Indeed, if you’re even remotely interested in the origins of this series, I suggest gritting your teeth and giving them a try.

The first Fallout is a harsh and unforgiving game; the entire thing is set to a timer of 150 days, which sounds to be a long period of time but will feel punishingly brief by the end. Nevertheless, the in-game world is pretty massive given this was a game made in 1997, and is rich with interesting characters, sub-plots and sidequests, and weird shit. Like, the kind of weird shit that ended up being a possible progenitor to the entire series. Great game; I certainly had a blast with it. The second game was much better in all respects, with improved mechanics and better controls, while also introducing some of the cornerstone narrative elements of the series, like the NCR and the Enclave. And, again, I made my own fun with the world in ways that were probably expected by the creators in the same way Bungie probably expected players to teabag one another.

It was lucrative, though.

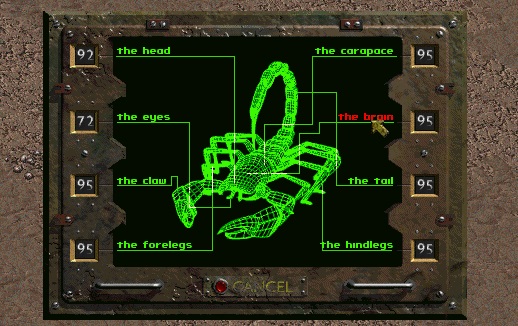

The common thread throughout all of this, I hope it’s clear, is that these games thrive on giving players choices about what they want to do in the world, and then making those choices feel significant. It also lets you decide what kind of person you want to be; sure, you’re the saviour of this wasteland, but perhaps you’re an arrogant prick about it all. Maybe you’re just a simple man named “HELK” who wants to bash “scorpins'” heads in with his bare fists. The games don’t just let you do it, they accommodate those choices and adapt accordingly, helping to maintain the suspension of disbelief required to immerse yourself in the world. This is as much a core part of the Fallout RPG games as Vault Boy, Deathclaws, and people standing waist-deep in tables.

This is why Fallout 4 was so terrible as a Fallout RPG, and probably why new players in the series starting with 4 didn’t understand the backlash to it; because, let’s be fair, that game was a dumpster fire. Bethesda tried to mash together the freedom of a Fallout RPG’s “blank slate” character with the kind of character-focused RPG protagonist of something like Deus Ex or The Witcher. The sad thing is that it actually had all the right elements for an excellent story under the character design of the previous games. However, Bethesda was too afraid that players wouldn’t correctly experience its three carefully crafted stories, and the Minutemen, that they removed that player agency. The result was your character listing off bland, lifeless dialogue for the sake of keeping you on track toward an attempt at a heart-string tugging storyline that didn’t even require that kind of restriction.

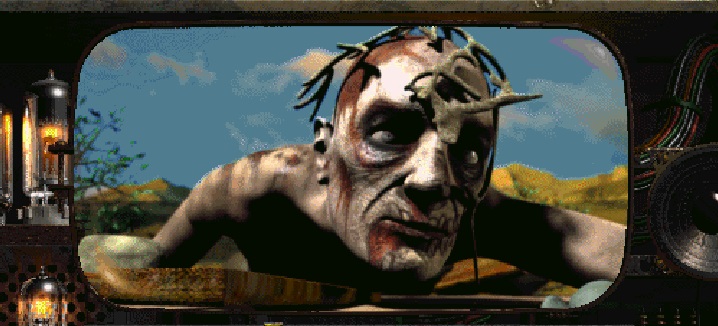

Pictured: A dramatic reenactment of my reaction to the disappointment following Fallout 4’s release. Metaphorically, I’m the baby. Mentally, too, probably.

By that same token, I’m actually looking forward to Fallout 76. While I love Fallout primarily for its stories, and overarching narrative, I also just really dig the world of Fallout. The kitschy retro-futuristic style and optimism of the ’50s-’70s taken to extremes has always appealed to me, especially when undercut with the trademark grisly humour of the series. An action FPS with that veneer sounds good to me, especially if it’s designed with that kind of game in mind, which is exactly what Fallout 76 appears to be, at least from what we’ve seen so far. I’m okay with a Fallout game taking the form of something other than an RPG, just as long as it’s designed to be that kind of game and it’s not a main entry in the RPG series.

I might not have liked Fallout 4, in fact it would be fair to say I hated it; however, I still played it for 147 hours. I love this series, I love it so much it hurts, sometimes financially, and it’s hard to stay mad about just one entry in the series when there have been so many story retcons and design changes throughout its history. Not to mention Tactics and Brotherhood of Steel. When Fallout 5 inevitably comes out, hopefully, Bethesda will have worked out their issues with trying to make everything an action shooter, made a better engine and hired some decent writers. Even if they don’t, it could still all be forgivable so long as the meaningful impact of player choice is returned because, without it, Fallout is just a neat aesthetic. Nevertheless, you can bet your bottom cap that I’ll be playing the crap out of it regardless. And that is why I’ll jealously clutch onto the soapbox about Fallout on this site until the day I rot into a ghoul.