Tomorrow, Arkane’s latest and arguably most intriguing game yet, Prey, will be released. For the uninitiated, this is a great time for fervent optimism, and the demo for Prey is available for Xbox and PS4 owners to try at this very moment. For the rest of us, it is also a time for some much needed quiet reflection on the game from which Prey takes its name. Developed by Human Head Studios and originally released in 2006, Prey is a horror-themed FPS that, in a twist of fate that has ironically become a defining characteristic of this franchise, was also a revival of a previously cancelled project from 1998. ‘Unique’ is a term that frequently gets bandied about to describe gaming curios from times past, but ‘oddity’ was and still is the best label to give the original Prey. Bloody-awesome, incidentally, is also a valid description. I recently made my way through the campaign of this decade-old gem and found myself blown away by how Prey truly is unlike any game that came before it – or any since.

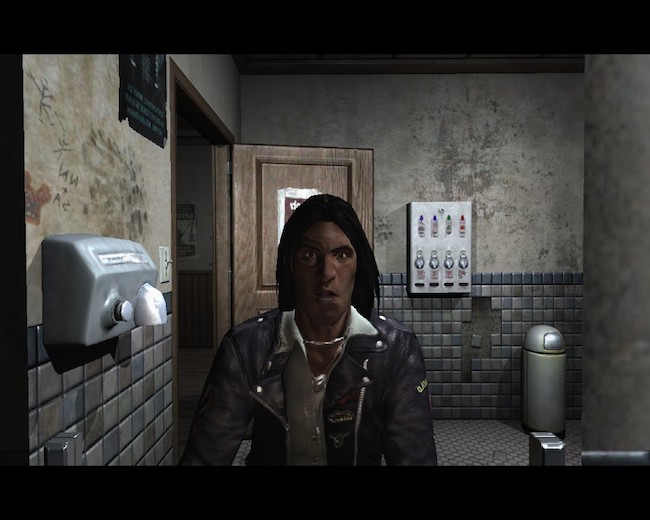

The story of Prey is better told than even my nostalgia would have me remember. Beginning in a grungy, badly-lit bathroom of a backwoods bar, the player finds themselves in the leather jacket of Domasi as he’s giving a monologue to himself in the mirror – he’s trying to pick himself up, but his tone points towards self-doubt and frustration. He doesn’t sound like he believes his own words. Domasi is a Cherokee but doesn’t care for his heritage and desperately wishes to leave his tribal reservation with his girlfriend, Jen. Jen is proud of her culture and runs her little roadside bar from within the reservation; even in spite of the leary red-necks who frequent it.

As he approaches the bar door, Enisi, Tommy’s Grandfather, approaches him attempting to command his attention. Tommy fobs him off, and Tommy and Jen argue their points of view until Jen is harassed by a pair of sleazeball hicks, drunk out of their minds, when the player as Tommy is prompted to pick up a wrench and attack them. Tommy beats both of the men back, likely killing them – it’s not made clear – when the lights come, and the coyotes outside begin to howl. The tension brought by the impassioned violence comes to a standstill as the television in the corner of the bar breaks to an emergency broadcast. The stereo begins to malfunction. Reports of lights in the sky all over the state are being reported, the television report states, and the jukebox suddenly beings to play “Don’t Fear the Reaper” as the roof splits open and beams of blue light begins to tear the building apart. Tommy, Jen and Enisi are all lifted into the light and wake up to a sight of pure terror. They are trapped on a conveyor belt, millions of miles above the earth, along with countless other abductees, and everyone is screaming. Everyone, except Tommy.

You’ve all ended up on a monstrous, fleshy planetoid spaceship that hosts a multitude of hostile aliens. They’re taking humans as a food source for the ship, but just before Tommy is sent to the butchers, the conveyor is sabotaged by a mysterious ally. Thus abandoned and separated from his loved ones, Tommy sets out to rescue them.

Prey’s opening moments are, even today, stunningly well scripted and full of subtlety that is rarely seen these days in this genre. The journey that Tommy follows is one filled with typical video game character archetypes but with interesting enough plot twists at well-placed points that it would be unfair to mention any spoilers, even for a decade old game.

The storytelling in Prey does a few things many shooters, and in some cases, video games in general, have never attempted to achieve. Firstly, it portrays Native American characters in not only a respectful way but an enlightening one. Tommy is not a tomahawk-wielding ‘noble-savage’ ripped from the pages of 1940s dime-store pulp fiction. He dresses in modern garb, has a complicated relationship with his ascribed culture, but is willing to change his mind over the course of the game. Another thing Prey’s story does exceptionally well is in its use of phantasmagoria and truly chilling moments of both participial and experiential horror. There a few scenes involving the brutal murders of children, which as a parent to be, made me pause for a day until I was sobered enough to return. Another moment unlike anything I’ve experienced in a game before is a genuinely gut-wrenching act of mercy-killing. It’s not a scripted moment; a man, naked and covered in blood, has lost his mind and is screaming and raving in a tone so shrill it turns the stomach. Tommy asks him what’s wrong, but the lack of reply humbles him. I decide to put him out of his misery, and Tommy apologises. I needed another break after that one.

The storytelling is not without glaring flaws, however. The mystical narrative elements do seem a little bit hokey in parts, yet they are in fact parts of Cherokee mythology, albeit cherry-picked and somewhat homogenised. Tommy’s refusal to accept his culture as anything other than bullshit in spite of being brought back from the dead by the spirit of his ancestors, though, is a laughably contrived character quirk. It only lasts the first few chapters, so it’s easily forgivable. There’s plenty of little moments that help define Tommy as a character that makes me miss the days when FPS protagonists had predominantly speaking roles. It’s worth wading through the buckets of Tommy’s potty-mouth reactions to uncover a subtle jab at DOOM 3’s darkness-drenched level design.

Even more atypical than its storytelling is the gameplay of Prey, which has a bizarre mix of gravity-manipulation puzzles, arena shooting, 6DOF dogfights, and the use of portals a whole year before GLaDOS ever came to taunt anyone with her deranged passive/aggressive quips. The weapons of Prey are all biological – that is to say, they’re all actually living aliens and are animated with appropriately creepy verve. The assault rifle’s scope, for example, is actually a tentacled leech that lunges at your eye every time you zoom in. Grenades are three-legged glowing crabs and are detonated after you tear off their legs. This theme extends to the entire arsenal, and it’s a refreshing feeling to seek out new weapons – not just for the sake of fire-power but to see just how weird the critter providing it looks. There’s only a handful of guns, but they all have multiple firing modes. However, despite all their unique looks and gross-factor appeal, they all fall into fairly standard weapon types. Full auto assault rifle, sniper rifle, chaingun, grenade-launcher, etc. Enemies, too, fall into familiar categories. Regular soldiers equipped with rifles and grenades, dogs who’ll charge at you, as well as a few mini-bosses/bullet-sponges to punctuate the end of each act.

The gravity puzzles are a damned hoot. Their implementation highlights the ridiculous amount of care that went into making sure the initial stages serve as a thorough tutorial. I say this because some puzzles will have you re-orienting the gravity of a chamber or room by shooting a switch. The slow roll of a level’s gravity from one side to another is ALWAYS disorienting. Some sequences are likely to give you motion sickness if you’re prone to it. After only a couple of levels, though, I found that even as puzzles became more complicated, I didn’t operate on as much trial and error as I did in the beginning. There are also heaps of these puzzles to be had, so much so that it generally feels that combat is more punctuation to the brain-scratching, rather than the reverse which is more typical of action games in general. It’s not all about nearly losing your lunch, though. Some sequences in Prey give you control over aerial vehicles for some by the numbers aerial combat and some gravity-gun style debris removal. There are also trippy set-pieces made with the use of portals, but the overall effect of these will be less impressive if you’re a fan of Valve’s puzzlers.

Lastly, while dated, Prey’s visuals are still effective because the doors of the spaceship you crawl around in throughout Tommy’s journey are human-sized anuses and vaginas. I shit you not. Body-horror, oh yes.

Prey is a shooter that deserved a wider degree of fandom than it received. With a trail-blazing use of new technology, atypical themes and characters, and a focus on smarts while also providing fast-paced blistering action, it is a game that is still very much worth playing today. If you can find a copy of it on online, don’t hesitate.