Well, uh, it’s Factorio. I’m glad we both agree because there is no argument you could make to disprove this objective fact. There is no better game, and if you disagree, you’re either choosing to be ignorant or so far down the rabbit hole of delusion that you enjoy the taste of black liquorice. It’s the best game ever made, full stop, end of discussion. Why bother with other games when we could purchase one and be done for the rest of our lives? Why does PUBG consistently outsell Factorio? Why is the heat-death of the universe inescapable? Because people are wrong, that’s why.

There’s the pervading feeling that all critiques of games, whether they be of the same genre or not, harbour an ideal game in their heads at all times. Because of the variety of people writing reviews, this has culminated in a strange impression that a ‘perfect game’ could exist. This can’t happen, but there’s a strong case to be made for the ideal attributes a game should possess. But if there are ideal attributes, then a game with all of those traits should be the perfect game, right!? Well, no; I just said that the perfect game couldn’t exist. Stop being so wrong, you wronger.

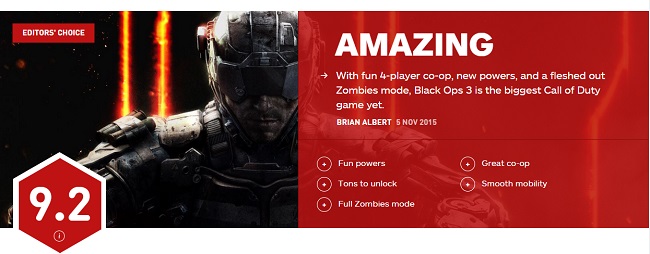

Have you never read IGN? A 10/10 is a masterpiece, not perfect. Duh.

Game Numbers

Game reviews have often presented the medium as achievable of perfection. Reviews have carried numerical scores, and these are readily applied between genres without justification for why it’s a sound comparison. We end up with places like IGN giving out 7.8’s to games that offer wildly different experiences. Aggregate sites, like Metacritic, compound the issue by applying this numerical comparison (or creating one when a site doesn’t supply one) between mediums. It’s tempting to think that there is an objective metric behind these numbers that could yield guidelines in creating the perfect game, but it’s not that simple.

When we talk about the perfect game, we’re talking about something that is complete and flawless. It’s not missing any components to be enjoyed to the fullest, and it has no faults in its design or execution. Regardless of what genre or context it exists in, this game cannot be faulted by anyone. It is, universally, a perfect game, enjoyed by IGN, Polygon, Eurogamer, Edge, and everybody else as a perfect 10/10 experience. The problem, of course, is that we live in a reality where perfection can’t exist.

PUBG is played by a lot of people, but it’s far from perfect.

As much as I wish Factorio were, in fact, the perfect game, it’s not. People are varied, and tastes change from person to person, like how everyone other than me thinks The Beatles were good. Similarly, games come in all shapes and sizes, ranging from grind-heavy MMORPG’s to action-packed FPS’s. As gamers, we want to find the experience that scratches that itch we have in the back of our brains, and the kind of game that can reach back there won’t be the same for all of us. Different designs achieve different experiences, and they will appeal to different people to varying degrees. No one game is going to appease everyone, but we know we can identify traits that are ‘good’ across all games, which is… Weird.

While there can’t be one supreme ruler of the video game empire, we readily identify things that make a game good or bad. A lot of what we critique isn’t dependent on the genre, including how well optimised or responsive a game is. Hell, even critiques within genres are applicable more generally, such as the variety of characters in a fighting game being comparable to the variety of classes in a hero-shooter. Intuitively, it seems like we can take these critiques and ensure we follow them to make the perfect game, right? After all, once we exhaust any faults our new game can have, we should be able to deliver a complete, perfect experience. Weeeeell, good luck making it ‘complete’.

Big, maybe, but not complete.

People Like to Chunk

One of the reasons we can’t make the perfect game is because creating a ‘complete’ game is a bit harder than you think. To make a ‘complete’ game, every other game must be encompassed within it. Sure, the perfect game can be flawless, but think about how many genres there are and the sheer variety of gameplay each one offers. By the time your Survival-Racing FPS MMORPG VN RTS 4X Twin-Stick Shmup Metroidvania Management Text Adventure comes out, you’ll need to add on a Battle Royale mode, and like hell you’re calling it complete without a fishing mini-game. It’s like saying that you need every flavour of ice cream in a scoop while still being able to taste every flavour at once. It just can’t happen; everything liquefies into a hot mess of salted caramel and sadness. We design games with a tailored experience in mind, namely a genre, and then go from there. To make a ‘complete’ game that appeases everyone is impossible, but humans just kind of think that way.

It’s a failing of humanity that we rarely talk in specifics. We categorise, generalise and stereotype instead of being detailed in our conversations, and this extends to comparing games. Steam reviews are lumped into a single phrase, like “Mostly Positive”, and it’s only by scrolling to the ever so helpful written reviews that you gain any insight. GoG works on a 5-star system, and IGN has a 10-point system, but these don’t distinguish between genres. It’s not an enormous leap of logic to conclude that using these numerical systems imply that a perfect game can exist. The problem is that these objective metrics fail to capture the biased viewpoint they originate from, and that poor reviewer will never find a perfect game to give a real 10/10.

Even this masterpiece only got a 3.5/4 back in ’99.

The apparent reason we give ‘perfect’ scores or imply that such a ‘perfect’ game could exist is that you already know perfection can’t exist. If I get the point across to you that something is AMAZING, that’s all that matters. Humans can’t identify the exact wavelength of a colour based on sight alone, so we live in shades of red, green and blue. It’s only natural, then, that we would take a system so precise as fractional integers and apply it to the cause of reviewing games, like barbaric cretins with no moral compass. We label games ‘perfect’ because it’s convenient, but it’s a crappy way of assessing games.

As far as I’m aware, no one treats different genres the same. God of War and Dark Souls share a lot of similarities, but it’s a bit of a stretch to compare them to Command and Conquer. The part of my brain that releases dopamine can be triggered in multiple ways. The joy you feel from carving open an undead step-uncle’s skull is different than when you solve a Zachtronic’s puzzle, even if both are satisfying experiences. To put these games on one universal scale is absurd, and to imply that one game could appease everyone is equally nonsensical. So, is there an alternative framework here? Well, as a guy who needs a way to rationalise learning Aristotelian ethics beyond engineering, sure! Why not!

Time to think like a porcelain head!

So Dumb It Might Just Work…

Back when Ancient Greece wasn’t ancient, there was an old bearded philosopher named Aristotle. To put it lightly, he did a lot of thinking about things that no one cares about, including practical ethics. His theories led to what we understand today as ‘virtue-based ethics’, a moral framework that’s more about function than godliness. The core idea is that you, as a thing, have some function/purpose (translated from ergon) peculiar to you that only you, as that thing, can do. Your excellence/virtue (arete) is exemplified in your ability to perform your function well. For instance, a clock’s function is to keep time, so an excellent clock keeps time accurately, requires little to no maintenance, etc. These qualities are the virtues which permit the clock to function well, but video games aren’t clocks, now are they? Don’t worry. We’re getting there.

Aristotle saw the function of human beings as ‘to act rationally’, so whatever virtues we held should be in the name of rational thought. The problem is that people are varied, and what allows an Olympic athlete to achieve excellence is different to a computer scientist from MIT. Our old Greek friend devised the idea of a virtuous mean, meaning virtues can shift in magnitude but never be pulled into vice territory. Both the athlete and the coder need to maintain self-control (a virtue) in their different diets (i.e., different means), but neither should over-indulge or stop eating (which are vices!). That’s all well and good if we’re trying to develop an accord of 2600-year-old morals, but what the hell does any of this have to do with video games!?

Perhaps the same could be asked of all computers.

Let’s think about the function of video games: what it is that they do that nothing else does. Actually, no, that’s way too hard. Plan B: Let’s think about the function of video game genres. It’s a lot easier to wrap your head around what is unique to a genre than an entire medium, and it should be evident that a Metroidvania holds a different function to an FPS. These genres are not designed to be played the same, nor are they after the same responses from the player (unless you have an FPS-Metroidvania, but let’s not go there). The virtues between these genres will be different, and we’re not implying that a perfect game can exist, just excellent ones.

By framing our assessment of video games in terms of virtues, we can hint at what makes a game excellent without falling into the trap of perfectionism. Being virtuous doesn’t make you perfect; you can’t be excellent at all things all the time, nor can one game be excellent in every single genre. Different genres will strive for different virtuous means, so even though Starcraft and Crusader Kings 2 are both Strategy games, their virtuous means for ‘breadth’ and ‘depth’ will differ. You could even have a few virtues that cross between genres, like ‘variety’ and ‘optimisation’. Of course, this might all feel super obvious because we already do it.

Believe it or not, ignoring cons doesn’t make you an excellent reviewer.

Reviews have become more nuanced in modern times, and how summaries are presented has evolved as well. I remember when gaming magazines would give a final number rating based on the average of other number ratings that were vaguely related to the written review. These days, final scores come with dot points, summary comments, pros and cons, and that’s not even talking about video reviews. It seems we already pin down the virtues of a genre, but we utilise (sometimes arbitrary) numbers for convenience, and that leads us full circle. If you’re going to employ alternative methods only to then boil everything down to a numerical score again, it’s a bit self-defeating. This, along with many other reasons, is why Gamecloud no longer hands out a numerical score, but keeping the pros and cons still hints at what we find virtuous in a genre. It’s not a perfect system, perhaps, but it’s not like perfection is attainable.

Final Thoughts

The idea of ‘the perfect game’ doesn’t come from people believing there is one. It arises from a misapplication of numerical metrics without any basis, but it’s not like humans would use them any other way. Instead of using a system based on implications of perfection, we could think about games in terms of virtues, the qualities that make them excellent. I’ll bet Aristotle didn’t think some mid-twenties dweeb would apply his work to video games, but here we are. I’m not sure what the takeaway from this article is, but nothing’s perfect, right? Wrong again. Factorio. End of discussion.