Reading is not one of my strong points. There’s a comedic irony to the fact that I write for GameCloud but can barely manage to get through a couple of books each year. Maybe it’s because I’m busy with uni studies or because my brain hates words, but I can’t seem to get into the whole “words on paper” trend. Images, on the other hand, I have no problem with. Give me comics, movies, anything with a frame and a picture to work with; that’s the stuff that rides right into my memory sacs on a glorious lemon-scented chariot. If only there were some game-related solution that combined both of these approaches into one waifu-soaked package…

Visual novels have existed under the radar for many years, but as games have grown more popular, so too have visual novels. While never soaring to AAA heights of popularity, VNs like Steins;Gate, Ef and Clannad were popular enough to achieve overwhelmingly positive reviews, not to mention their respective anime. It’s great to see variety in games, but all the VNs I see seem to be weeb fetishes that cater to a, uh, particular taste. On top of that, these aren’t the most compelling systems on the planets. They’re just novels with pictures. Well, time to take a deep dive into what these strange video game books are all about.

This article is really just an excuse to post really weird screencaps

Page Turners

If you’ve ever wanted to read a book but still play a game, VNs are right up your alley. They’re a more chilled experience than your regular FPS, typically presenting static imagery and words instead of flashy cutscenes. The label is purposefully broad because of how weird some of these games get, but a focus on story over gameplay typifies them. Unlike Telltale games, they only offer the occasional choice to the player after copious amounts of reading, so there’s very little pressure to play the game. What gets me is that while there are branching narratives to explore, you don’t do much beyond clicking the screen to turn the page. Where does the appeal lie for a game without gameplay, though, and how did such a format come to fruition in the first place? Well, it all started in the mystical and often bizarre land of 1980s Japan.

Back when Eurhythmics were still popular, adventure games were taking their first steps to world domination. Games like Mystery House and King’s Quest were looking beyond coin-guzzling arcade cabinets and asked players to use their brains for once. There was nothing else quite like these games at the time, and Japanese devs were taking notice. Games like The Portopia Serial Murder Case more closely resembled these early adventure games than contemporary VNs, and it wasn’t until the ‘90s that the genre solidified. Misty Blue, Metal Slader Glory and (from Hideo Kojima himself) Snatcher experimented with the format, with a focus on narrative over deep mechanics. Fast forward to today, and the influencers have become the influenza. Or something like that.

It certainly has the capacity to go viral, at least?

By the way, for a fuller look into the history of VNs, I recommend this article, but you’re not here for a history lesson, right?

Today, VNs are still a niche format, but one that’s gaining popularity in the West. VA-11 HALL-A was released to almost universal acclaim (for good reason), and Phoenix Wright is a beloved American classic. The games of today still focus heavily on narrative over mechanics, but modern VNs commonly incorporate simple mechanics to keep the player involved. These are still mostly non-interactive games, lacking the depth of RPG’s or potential freedom in battle royales. It’s easy to dismiss the genre as the weird incestuous cousin of better games, but they wouldn’t have persisted without appealing to someone.

Two Good, One Bad

Not to state the obvious or anything, because lord knows I love doing it, but people like stories. If there’s anything you can glean from the success of movies, Netflix or regular old books, it’s that people like to get swept up in a story. We form schemas from friends’ tales, we learn from fictional parables, and we form our view of the world through inferences of cause and effect. While VNs don’t generally offer deep gameplay, they rely on the strength of their storytelling to connect with a player. Of course, it wouldn’t be much better than a book if these games didn’t offer agency.

You know. Choices.

One of the big selling points of VNs is their ability for you to explore a non-linear narrative space. Branching narratives are a tactic used to appeal to a broader audience, and it gives a choice to the player to take a more exciting route instead of being stuck with a book they don’t care for. It’s not too hard to implement either since all you have to worry about are static images and words on a screen. Why hasn’t this broad selection of storylines led to the mass appeal you might expect? Well, some people are just the worst.

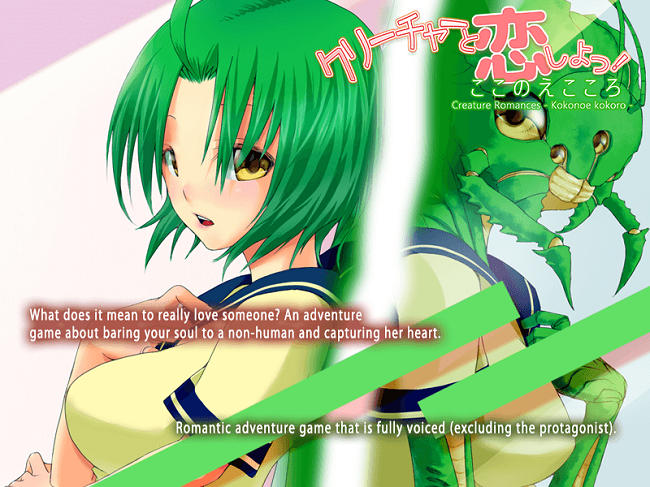

Part of the success of visual novels can be traced back to erotic content. Dating sims are almost synonymous with VNs in the West, and most branching narratives are based around moe archetypes. The reason behind this is because while VNs make up a staggering proportion of video game sales in Japan, they appeal to an otaku audience. The term ‘otaku’ isn’t meant to flatter either, describing social outcasts whose obsession with anime tiddies borders on traumatising. The term has become a bit less hated as of late, but these guys make up most VN sales, so the genre is drenched in eroticism to keep the target audience pleased. So, VNs worked it.

Or, should I say, flaunted it

Leaning In

The audience is already set in stone, kind of, so what we see more of these days are VNs that poke fun at the format. Hatoful Boyfriend is a visual novel all about dating pigeons, but each one follows the same moe archetypes as every other VN. Dream Daddy flips the archetypes on their head by having hunky dads instead of cute girls as your target of affection. These games don’t try to tear down the genre but instead pay homage to it, all the while poking fun at the stupid traditions that have evolved within the medium. Parodies tend to work that way. It’s a fun way to handle the less positive side of VNs, but sometimes things need to go further.

There are also VNs that go entirely against the grain. Doki Doki Lit Club hides a horror game under a weeb-lathered surface. Long Live The Queen is a weirdly deep game that requires understanding mechanics so broad that you’ll need regal training to stay alive. Neither of these entries strays far from appealing to the audience of anime-obsessed dorks, but they do challenge core aspects of the standard VN. One pulls the rug from under you towards the end, and the other takes the rug and beats you with it until you do your maths homework. Taking from VNs rather than becoming them is a smart way to handle avoiding the stigma, and it’s not like other genres aren’t doing exactly that.

Blazblue is a great example of using VN techniques in a game that isn’t a VN. Well, not in the parts that it’s not a VN, at least.

We’re seeing more and more of these techniques venturing out into other games. Persona, while far from a visual novel, employs many of the same methods. Each character embodies some archetype, i.e., the literal embodiment of a tarot card with a personality to match. These games don’t skimp on the reading either, nor do they cop out with their branching narratives, so they’re kind of like a visual novel in a different context. They don’t have static imagery, but they have all the markings of a VN taken to the next level. The problem is that Persona is a game so highly polished and well thought out that it’s a diamond in the rough, and not all games need to take from VNs.

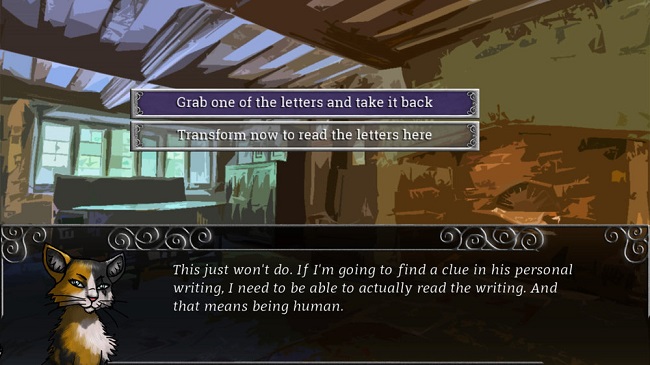

While other games can pull from VNs, one thing they almost never achieve is branching narratives. Multiple endings are fraught with peril, let alone wholly optional storylines, but VNs offer the perfect medium to allow them to be used. Recycled images are fine in a VN because of the nature of the game, but changing the colour palette on an enemy in an RPG is just lazy. Because a visual novel is more reliant on its story, more effort can go into polishing the narrative structure, as opposed to other games where mechanics drive the experience. If you can pull off branching narratives in your game, great, go for it, but holy weeb-balls it is not likely to go well for you.

None of this is to say VNs always have great choices

Final Thoughts

Visual novels are not the irredeemable pit of weeb and anime that many people (i.e., I) think they are. There are plenty of games that poke fun at the genre, and they offer a robust way of creating a branching narrative that doesn’t suck. Sure, there’s a lot of terrible VNs out there, but the genre need not be exiled because the target audience is obsessed with two-dimensional ladies. We can exile the target audience instead. Those guys are the worst. They can, like, read and stuff. Gross.