After a solid fortnight of doing nothing but learning about refrigeration cycles (wooooooo…), I hopped onto my computer and noticed Scott Ludlam in my Steam friends list. Huh. How curious, I thought to myself, equal parts confused and ecstatic that someone of such renown would add me on Steam. Upon further investigation, it wasn’t him. I had been cunningly deceived and was, naturally, distraught, like a ham sandwich that was hit with a golf club while being eaten by a toddler. After applying common sense, I realised it was my inferior friend posing as him, stealing (adopting is too generous a word) the name of a man who had earned his spot on my friends list through hard work and a viral YouTube video. Before planning my revenge against Fake Ludlam, I started thinking about pseudonyms in video games.

Pseudonyms are a strange thing to think about because, nowadays, they’re just so… Normal. If you play any game online, you’re not given a generic identifier like ‘Player 1’ or ‘Red A’, you choose what your name is, and that’s a standard practice. That’s weird. That’s seriously weird. Why does it matter to name ourselves in games when naming ourselves doesn’t do anything!? I can understand wanting to be recognised, but you could do that with generic ‘P1, P2’ indicators too. So, why do we let allow customised pseudonyms in games? Because it’s more fun that way, that’s why.

Anonymity and pseudonymity are the all important tools keeping that safe distance between you and that random guy on your Steam friends list. You don’t want everyone knowing your real name, address, phone number, email account or even name, so hiding behind the veil of anonymity is sensible. In video games, pseudonymity is far more common than true anonymity because, well, scoreboards would be impossible to interpret if no one had a name. Most people will adopt one pseudonym across different games, donning iconic and recognisable names like ‘Day[9]’, ‘PwnageMachine’, or ‘xXMoMsLaYeRXx’. Pseudonyms in games have been around for almost as long as video games themselves, which has led to some weird (but funny) consequences.

Consequences.

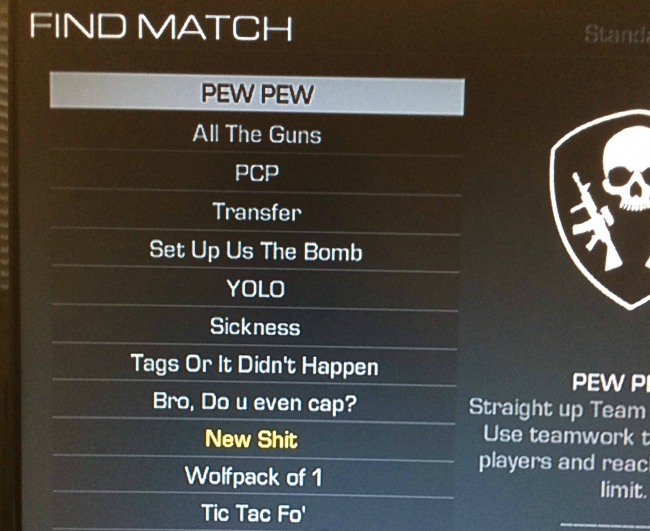

Ever since the top score on Donkey Kong belonged to ‘DIK’, people have been creative with pseudonyms. This includes names commenting on trends and legacies (360NoScopeDorito), names constructed in l33t (360N05c0p3D0r170), and names that use the game’s own message delivery to poke fun (TenThousandSmallDogs). They allow for recognition without sacrificing anonymity in an online game, a necessity when you get death threats for playing Elven Archer sub par. A lot of games will ban users with offensive names, but there’s still a whole lot of freedom when it comes to picking an alias. This freedom of identity has also led to a freedom of speech within the games we play, regardless of how anonymous we really are.

Anyone who’s played DotA, LoL or CoD against ‘that guy’ knows that people hidden behind a veil of anonymity can be dicks. Anonymity and pseudonymity themselves don’t immediately make people awful (I’ve met lovely people in DayZ and World of Tanks), but it certainly can bring out a darker side of them (like some people I’ve encountered in DayZ and World of Tanks). Still, people act differently when they’re somewhat anonymous, and video games have practically standardised pseudonymity. So, what makes people act the way they do, and why has pseudonymity pervaded the medium for so long? Trolling. Trolling is why.

Trolls, the aggravate-because-we-can-ers of the internet, have always fascinated scientists and YouTube commenters alike. Masked behind the veil of pseudonymity, wreaking havoc without remorse, they are the logical inevitability of the online disinhibition effect. The ODE vomits the theory that since the troll knows they’re anonymous and that the internet is a lawless, vapid wasteland where you can say just about whatever you want without consequence, dickish behaviour is just bound to happen. It’s science, and it’s a pleasurable activity to take part in. So, for video games, the perceived anonymity that arises from pseudonyms, combined with the nebulous enforcement of social standards online, is a breeding ground for trolls. This effect is then compounded in games because they’re competitive. Yay.

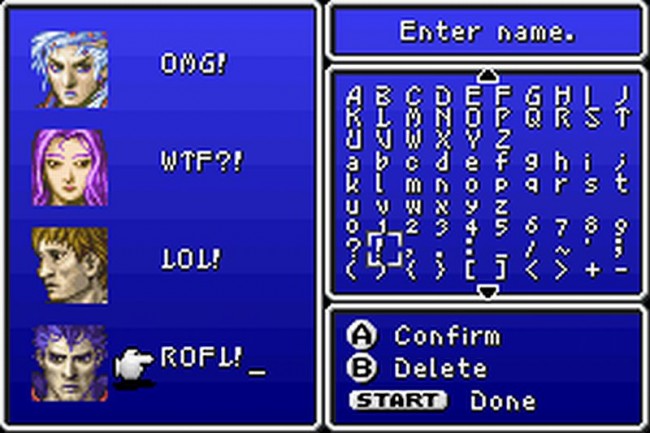

These are real names. Really.

Shockingly, a lot of video games involve winning, whether it’s against AI or other people. After a couple wins, you feel a bit more confident in your ability to wreck everyone else, and this happens the more you win. Of course, there are the people who feel overly confident and more skilled and more adept and more attractive and more human and just better than you. These aren’t the people who suggest advice, these are the people who charitably instruct it unto you because they’re on an incomprehensibly superior level and are so much more god damn meta (so knowledgeable in the meta, they themselves are, in fact, meta) compared to you, you filth-flinging scrubtastic gougenut. Regardless of how often these players win, they’ll still see themselves as superior to you because, to them, they just, uh, are. It’s about the power trip of authority that is so rarely experienced in other areas of life, but it’s just a game, right? Yeah, and that’s why it happens.

Video games are designed to immerse the player (narratively or otherwise), and some players are willing to immerse themselves deeper than others. Pseudonymity in video games afford a player the chance to act as a new identity in a space that is completely unhinged from their own circumstances in reality. This immersion into a new identity influences how you think and act in-game. When I play Counter-Strike, I’m no longer Nicholas Ballantyne, the single 23-year-old male incapable of holding a rifle, talking to females without puking or hand writing legibly; I am GreyKill91, a silent-but-deadly mofo who don’t take no shit from terrorists with pornstaches. Now, when I don that name, I separate myself from what I do. I’m not nobody though, I’m GreyKill91, and GreyKill91 is more confident, more skilled and more vocal than Nicholas IRL. Even on a subconscious level, when you adopt a new name, you’ll start viewing yourself and acting differently, for better or worse. Call it escapism, call it immersion, your identity shifts, but this also means something beautiful will start happening…

When you pick a name, you are given the opportunity to craft how you are perceived by other people. This, in effect, makes whatever pseudonym you adopt a form of expression. You’re not just given a name, you’re free to choose one, and it’s good that it lets you. What this means is, clearly, whoever has the best name wins, because games are the sort of place where such meta-gaming happens. Collecting all the cheese in Skyrim, making the most disturbing Saints Row character and having the best player name in a lobby are all internet-famous meta games. Pseudonyms are weird though, because they don’t influence nor are they influenced by the game in any way. In fact, they’re not even related beyond identification, yet hilarious names keep cropping up. Meeting ‘The Brady Bunch’ in TF2 or ‘Obama’ in DotA is funny, but it doesn’t mean they’re inherently more powerful mechanically because they have incredible names.

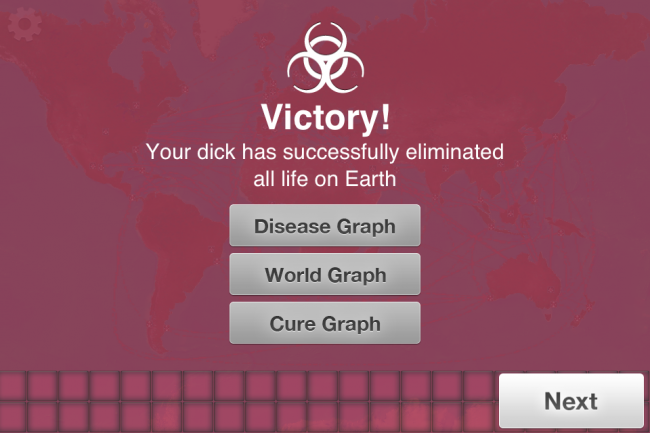

About 500 babies is still the same as one grown man, mechanically speaking.

One of the reasons ridiculous pesudonyms keep popping up isn’t just because they’re funny by themselves, they also serve to create a meta narrative involving ‘Whitney Houston’ laying the smackdown on ‘Dwayne -The Rock- Johnson’. When you’re playing TF2, the name of whoever kills you dramatically flashes up in front of you, as if to make sure the identity of your killer is burned into your mind like bad tasting existentialism. Suddenly, a story emerges. You, the more deserving and better dressed underdog, have created an adversary, a nemesis, an antagonist to overcome. There’s no benefit in killing that guy more than any one else within the game’s scoring system, but you know who that person is, and they need to die. The more shandonkulous the name of your adversary, the better the meta-narrative, and the more satisfying your victory.

It’s important to remember that anonymity can be just as (if not more) satisfying from a meta-narrative perspective. DayZ and Rust keep names hidden to get you more immersed into the game, but what identities do people have when they have no identifying features? We craft them in our head, obviously. That nameless guy running across the fields in a motorbike helmet? No idea who he is, but he’s clearly a threat, and his name is probably George. He looks like a George. By leaving so much left unsaid, we fill in the gaps of this mysterious stranger’s profile, but usually incorrectly. We typically fill in the gaps to serve ourselves, so we feel better when we performs less than pleasant acts on them. As for our nameless selves? We see ourselves like Blondie from The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly. We may have no name, but we make up for it in other ways.

A good name is still a good name though.

Without getting too Gödel Escher Bach on you, pseudonyms operate on a strange level where meta-gaming and anonymity collide. While a convenient solution to maintaining appropriate levels of internet security, pseudonyms have allowed trolls to breed at the same rate as names that turn the game’s feedback system back on itself. A medium for expression in of themselves, the pseudonym is often taken for granted, but without it, we’d never have such glorious tales of ‘The Harlem Globetrotters’ being head-shot by ‘tinyducksonfire’… Ah, the memories… Now, to kill Fake Ludlam.

Editor’s Note: The What, Why, and WTF is a fortnightly article series that explores the culturally pervasive elements of gaming, those parts of video games that seem to have left some mark on gaming as a whole or Nick just finds really interesting. It is in no way an academic source, despite liking to pretend it is.