Imagine someone punched you in the face after they declare that they’re a pacifist. Along with a sudden wet sensation in your nose, you might feel a bit confused by the message this fellow is trying to convey. When someone says they’re a pacifist, they usually offer tea or delightful home made biscuits, not a can of whoop-ass to accompany that knuckle sandwich with your name on it. Now imagine that instead of being the receiver, you are the messenger behind the punch. This might seem a little far-fetched, but this is just one of the wild things video games can do.

No, you’re not turned into a punching machine; you’re just put into a ludonarratively dissonant situation. The gameplay and story, while fine on their own, give out conflicting messages. Initially, your avatar is mulling over the loss of his companions and the pointlessness of war. Five minutes later, you’re blowin’ dudes up without hesitation and feeling good about it. It’s not entirely clear what you’re meant to take away from the whole experience; is war bad or fun? It’s a bit of a faux pas in game design, but when used correctly, ludonarrative dissonance can help to make a more thought-provoking game. It’s also an excessively fancy pair of words, so there’s a bit more to it than a simple story/gameplay mismatch.

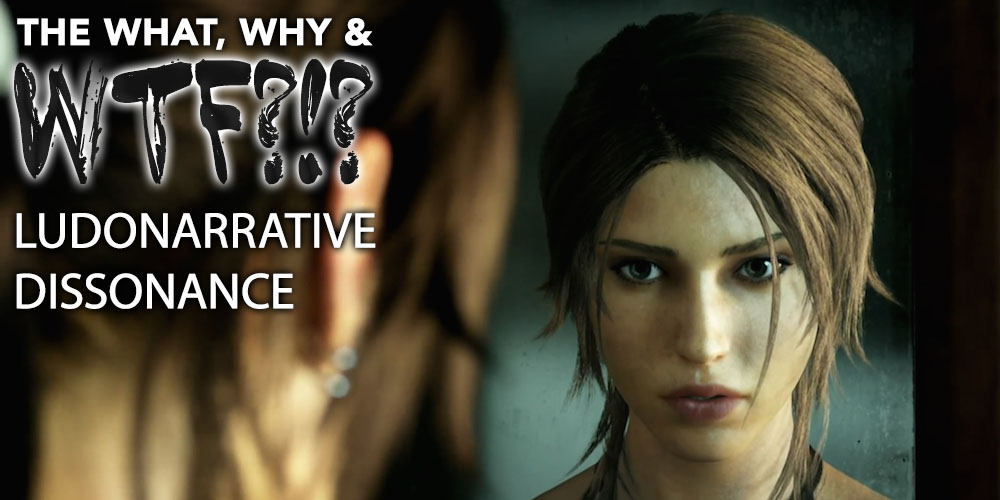

When an image goes here, this text will make a lot more sense!

In the academic analysis of video games, there are two broad approaches: narratology and ludology. Narratology is concerned with narrative structures of works, like films and video games, and understanding how they influence the audience. Ludology focuses on the ludic structure of games (i.e., the design of a game, it’s mechanics, etc.) and how it influences players. Although ludology is interested in the narrative of video games, it does so by looking at it through the lens of the game’s mechanics. It’s a bit like comparing the game’s cutscenes to the game itself, and this is at the heart of the excessively long and fancy term, ‘ludonarrative dissonance’.

Ludonarrative dissonance doesn’t just describe contradictory messages the game presents, it encompasses the conflict between two competing architectures. The guy who coined the term, Clint Hocking, used it in a blog post to describe the conflict that arose between the ludic and narrative structures in Bioshock. Hocking noted that there was an inability to pursue an objectivist self-interest narratively, despite the game’s mechanics implicitly aligning the player to such decision-making. In other words, while the mechanics encouraged a ‘seek power to progress’ play style, the narrative forced the player to ‘reject power to progress’. This dissonance was off-putting to Hocking and saw it as a flaw in the game’s design. Since the original post, the term has become widely used (perhaps to a fault) to describe these contradictions in story and gameplay.

“I wish to be friends. Have some nuclear warfare.”

It might seem convoluted to think of ludonarrative dissonance in terms of abstract designs, but it’s an important distinction from a simple story/gameplay mismatch. Not only does ludonarrative dissonance sound fancier than a Russian cocktail mixed by Vladimir Putin, it’s more focused on player allowances than obvious contradictions. Of course, most people just use the term to describe story/gameplay mismatches because it’s a pair of excessively fancy words describing excessively abstract concepts, and that’s totally understandable. It’s not wrong, regardless of what a linguist will say, and it still gets the point across that these contradictions detract from the game experience… But why?

The best films, novels, and video games are all logically internally consistent. If that logic is ever broken, like if Archer was suddenly a Raptor, it can be quite jarring and break the audience’s suspension of disbelief. In a video game, this is doubly so since both the mechanics and narrative need to be logically consistent with each other. Having both the ludic and narrative structures gel is key to inducing a state of flow and maintaining immersion. If these architectures don’t seamlessly blend into each other, it creates something like a hypocrisy in the game’s beliefs, which is possibly the weirdest sentence I’ve ever written.

Against killing, but fine with throwing bat-shaped shuriken into people.

Games construct a set of beliefs through the mechanics and the story by reinforcing actions in line with intended behaviour. If we complete objectives, the story moves forward, and we get rewarded through the mechanics (like money or points). These reward systems construct a system of beliefs within the game, like whether killing aliens is good or eating zombies is fantastic. While the narrative might tell you that eating zombies is bad, the game’s mechanics beg to differ, but the story won’t progress if you eat the zombies, but zombie flesh gives mad buffs, but you need to move forward, but BRAINS! These conflicting beliefs (and the reward systems behind them) are what create the sensation of ludonarrative dissonance, which isn’t so far off the dissonance experienced in our usual lives.

When confronted with cognitive dissonance (i.e., our beliefs and actions not lining up) in our boring everyday lives, people can cope in a few ways. If someone’s actions conflict with their beliefs, they can change their beliefs, change their actions, or just ignore it. Someone who wants to save the environment but drives a Jeep could justify the current Jeep situation (“I might need to take it off road some day”), actively remove the dissonance altogether and buy a Tesla, or just ignore the glaring hypocrisy. These are all valid ways of alleviating cognitive dissonance, but ludonarrative dissonance isn’t about your beliefs, it’s about the system’s imposed beliefs.

Or buy a puma instead.

When confronted with dissonance in video games, we react similarly to when cognitive dissonance shows up, uninvited and smelling of yesterday’s rent, to the never-ending party in your head. We can justify the dissonance (“It’s intentional”; “It’s not game-breaking”), change our play style to avoid or remove the dissonance from our game experience, or ignore it. Again, these are all valid ways of alleviating the dissonance, but this leaves us at the behest of the game. If we are not given the allowance to change our play-style or ignore the contradictions, we’re left to justify the dissonance, something we might not have the patience or tolerance to do. Then again, it might not be the worst thing in the world to, you know, be forced to think why it’s there.

Musicians have crafted songs through unconventional means, and authors have written strangely formatted books, but video games are… Different. Viewing a page in a book that’s completely blank is like needing to swap controllers to defeat a boss; It’s certainly not the norm, but it’s not contradicting itself either. There’s no real equivalent for ludonarrative dissonance in other mediums since other mediums don’t have two separate components. It’s not like a film can create contradictory beliefs beyond the images and dialogue not meshing, but video games have both mechanical and narrative elements that can conflict. Despite this fact, game designers have been reluctant to take advantage of ludonarrative dissonance as a storytelling tool.

“I’m not a killer…” – Lara before killing 100+ dudes.

Ludonarrative dissonance is avoided when designing a game because of the reasons mentioned above, but what if it could be used to a dev’s advantage? Video games can force players into uncomfortable situations, and ludonarrative dissonance can help foster that uncomfortableness. Faux glitches have been used as ludo/narrative tools before, so why is ludonarrative dissonance avoided so much? If your intent is to unsettle or confuse a player, then ludonarrative dissonance seems perfect, but this relies heavily on the player.

As I said earlier, when confronted with ludonarrative dissonance, players are left at the behest of the game. If you are intentionally forced to justify the dissonance, this relies on you justifying it in a way that the dev wants. If they are careful, a dev could succeed in making you think a certain way, but pulling that off requires Professor Xavier levels of telepathy. It’s also tricky to design, because coming up with something that isn’t a typical story/gameplay mismatch is, shockingly, tricky. I can’t even think of an example, and I’m trying to sell this idea to you. Still, if done correctly, a ludonarrative dissonance could make for an awesome addition to a game.

A game about psychological turmoil? I reckon we could slot some dissonance in there.

There’s a lot more to ludonarrative dissonance than just game/story mismatches, and I can smell the storytelling potential. Perhaps it’s just misunderstood, maybe it’s too convoluted to implement, but ludonarrative dissonance is something that I’d like to see more of. Mind you, when it’s bad, it’s obvious, but we managed to implement glitches into games, so what’s stopping us from ludonarrative dissonance? Probably the fact it’s called ludonarrative dissonance. I mean, seriously, looking at that arrangement of letters reminds me of some Lovecraftian eldritch horror too shrouded and dark to pronounce, the sickening name of a beast I dare not whisper in even the most well-lit of rooms… Ludonarrative dissonance. May as well call it Cthulhu; at least that’s easier to spell.

Editor’s Note: The What, Why, and WTF is a fortnightly an occasional article series that explores the culturally pervasive elements of gaming, those parts of video games that seem to have left some mark on gaming as a whole or Nick just finds really interesting. It is in no way an academic source, despite liking to pretend it is.