Trying to write a review for something like The Stanley Parable (TSP) is almost comparable to reviewing an Escher Painting, or trying to peel the layers of an onion off in order to find some perceived core (which inevitably leaves you in tears amidst a mess of onion), or drinking coffee after coffee and trying to play Surgeon Simulator 2013. In short, it’s difficult, somewhat painful and likely to cause some kind of logical wormhole in your psyche.

It is weirdly self-aware for a game; that’s because, in essence it’s not really a game, it’s a game within a game, and THAT game is so surreal through its experience-of-another-existence-through-the-subjective-experience-of-an-office that it feels more like you’re walking through an extensive art installation than having a real effect on the world around you. Instead, in TSP it’s not so much you that has an effect on the world, it’s the world that has an effect on you. You experience the world of TSP through the first-person perspective of Stanley, but with the non-diegetic voice of the Narrator constantly in your ear, sometimes offering a brief foreshadow of upcoming choices.

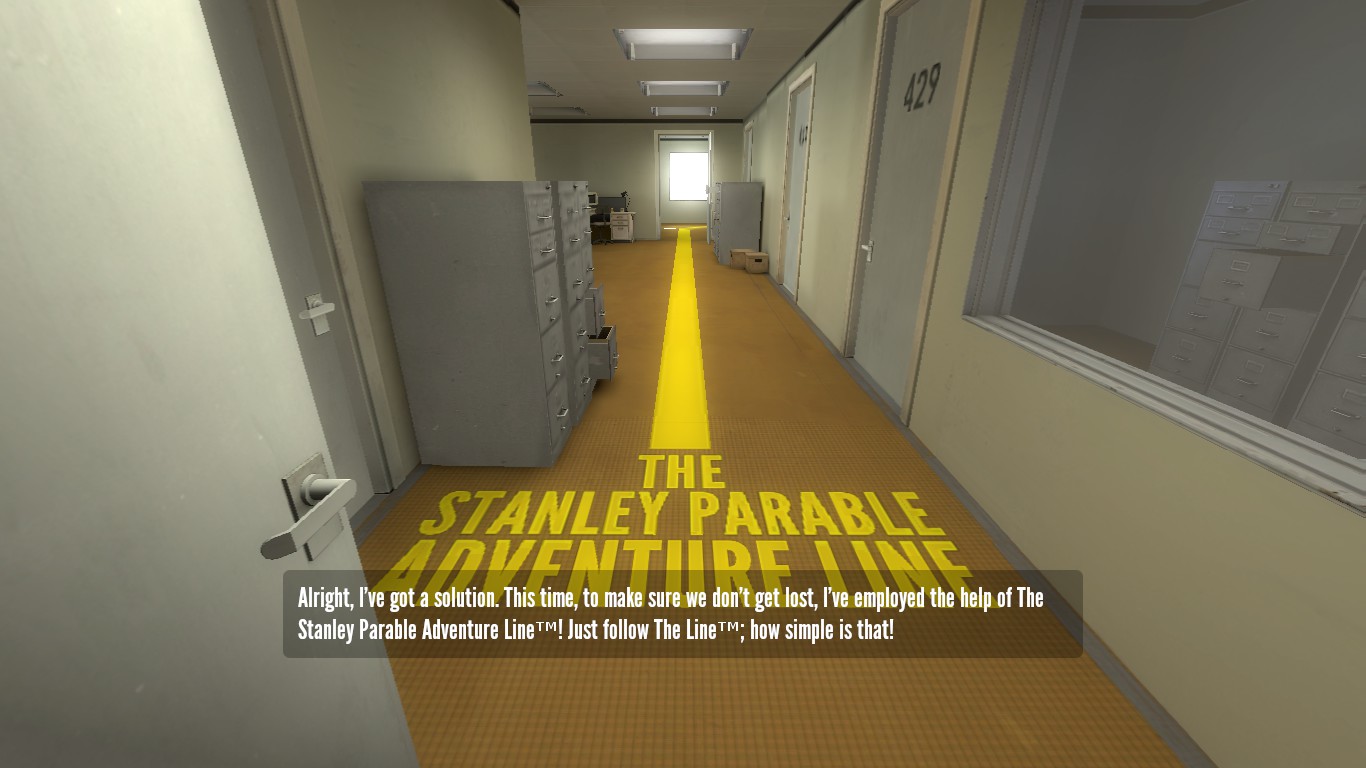

Perhaps more interesting than what the Narrator says is how he says it. His mood with Stanley varies greatly from amicable and jovial, to condescending and threatening, based on which decisions (or lack thereof) Stanley makes throughout the game. The decision-making process is something of an ‘Obey/Disobey’ dichotomy, and the player’s willingness to either obey the Narrator or rebel against him will often trigger a branching path of narrative that results in the story essentially writing itself as you discover what lay down the unfolding fork you have chosen, kind of like an old Goosebumps ‘choose your own adventure’ novel. In some scenarios, the Narrator takes an almost sadistic joy in manipulating Stanley, while in others, he expresses a shared frustration about inconsistencies in the world and how He himself is losing control of the story he is trying to tell.

As you may have anticipated, TSP is far more interesting when you choose the more rebellious options, though don’t be too rebellious- it may lead to your untimely undoing. If you keep to the path of absolute obedience, you might find TSP to be a brain-numbingly repetitive and sterile experience. However, it’s also the safest experience after all. It works incredibly well as a metaphor for the ‘straight and narrow’ expression regarding decisions we make in everyday life; you might not discover the greater significance of the world, and unfolding events, but you’ve done your little bit, you’ve kept your head down, done your work and are ready to switch off permanently.

Other people might not be so inclined to blindly follow orders; that’s where TSP really comes into its own. The game wants you to rebel, it wants you to transcend the safe choices we are all more or less constrained to in our everyday lives, in a world so closely resembling the real world for most of us. Maybe that’s part of the charm of TSP; Stanley’s so damn relatable- We all know someone who’s stuck in an office cubicle and hates their job. If you don’t know someone like this, well, go put on a copy of Office Space and you’ll get it. He IS you. His experience is what you dream about day in day out as you stare at the phone-book sized stack of paperwork, the endlessly ringing phones, the frustrating bosses. You just wish everyone and everything would disappear.

This is indeed a fascinating case as TSP is lacking two core components of videogame design; an achievable short and long term goal, and a form of currency. To elaborate on these two points, an achievable goal is essentially WHY you’re playing the game – In Super Mario Bros your long term goal is to rescue the Princess while the short term goal is to reach the flag pole at the end of the level. In Counter Strike and its many iterations, the short term goal is to either completely eliminate the opposing team, or rescue hostages, plant bombs etc.

The concept of economy is a little looser and more nebulous in definition- In the gaming world, it doesn’t necessarily equate to in-game dollars and cents, or the price you paid at the department store sale. No, in this context, I use the term ‘economy’ to describe the vital resources within the game that you must manage in order to succeed- in Super Mario Bros, your vital resources are your lives. ‘Saving’ them up requires skill and persistence and losing all of them will invariably quash your attempts of a successful rescue.

Within the Counter-Strike context, there exists both the more ‘traditional’ economy; ie: in-game monetary value expressed in dollars that is used to buy weapons and equipment, but there is also the far more valuable resource of your health. As there is no way to regenerate health lost from combat, it is the most valuable resource immediately available to you – without it, your player dies, and you are unable to aid your team until the next round. In short, your in-game economic assets are the things you value and strive to protect as, without them, you are unable to progress and will surely fail. Curiously, TSP is practically devoid of such economic assets and clear win/lose conditions. You merely exist in this barren office space resembling a rats’ maze, your only companion an omniscient narrator. Due to this, it feels more appropriate to ascribe TSP to the broader genre of “interactive fiction”, along with other recent titles such as Gone Home, than categorising it as a game.

Innovative take on interactive storytelling

Innovative take on interactive storytelling Provocative and compelling themes

Provocative and compelling themes Multiple & diverse endings add replay value

Multiple & diverse endings add replay value Players will question their own life decisions

Players will question their own life decisions

Nihilism goes from charming to depressing

Nihilism goes from charming to depressing Not really a “game” per se

Not really a “game” per se Tedious to explore all possibilities

Tedious to explore all possibilities

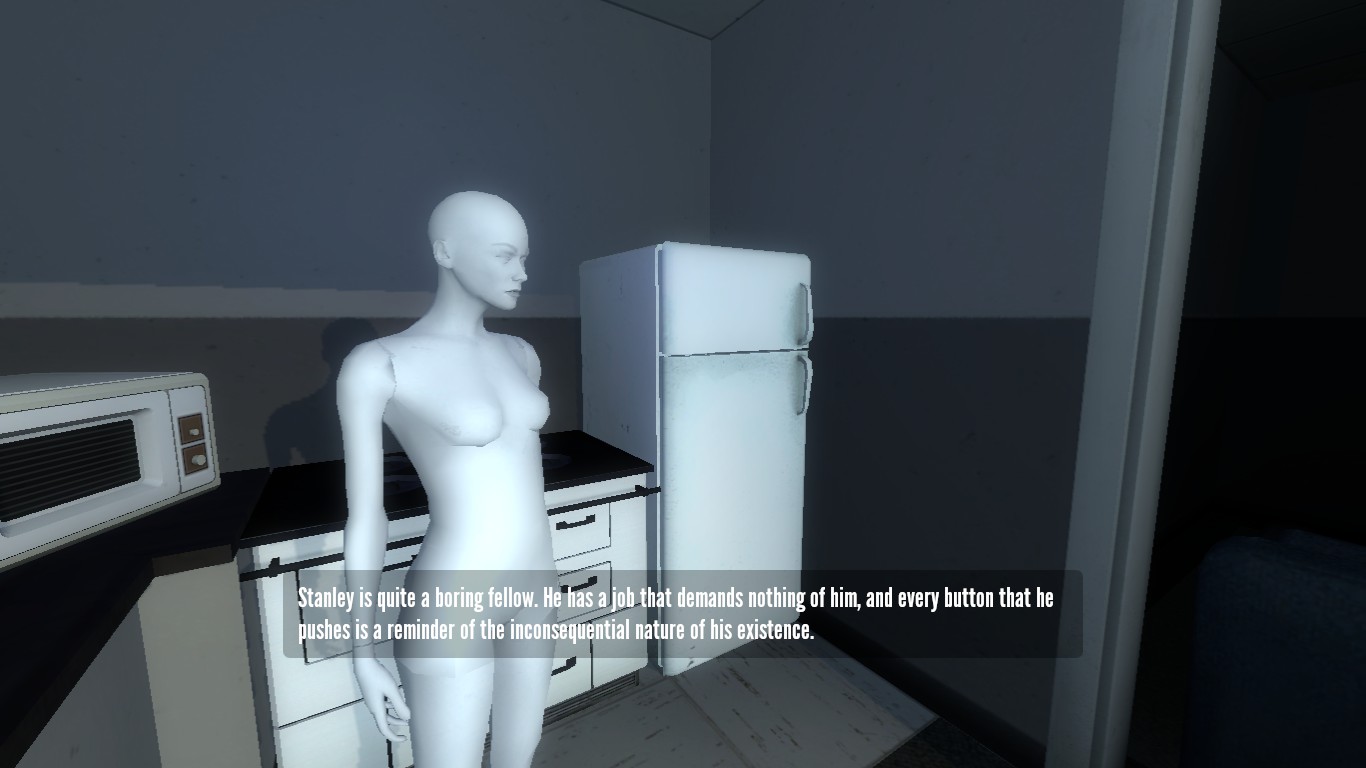

Overall, The Stanley Parable develops a sense of foreboding nihilism; that, whatever you do ultimately doesn’t really matter – Stanley is no action hero. He’s no Gordon Freeman, no Master Chief. He has no crusade, no purpose, nothing to fight for. His existence has become increasingly purposeless, almost like a character from an Albert Camus novel, only without the same degree of self-awareness. Essentially, The Stanley Parable is Absurdism in practice. There’s no trophy, so to speak of at the many ‘ends’ it concludes at. However, what makes this an important game is not about what you bring to the game, but what the game brings to you. It’s a game that tells you far more about yourself than most other games. Honestly, i’d recommend that you go grab a copy, pour a drink, play through a few times and take a quiet moment to reflect on your choices, yourself, and your life.