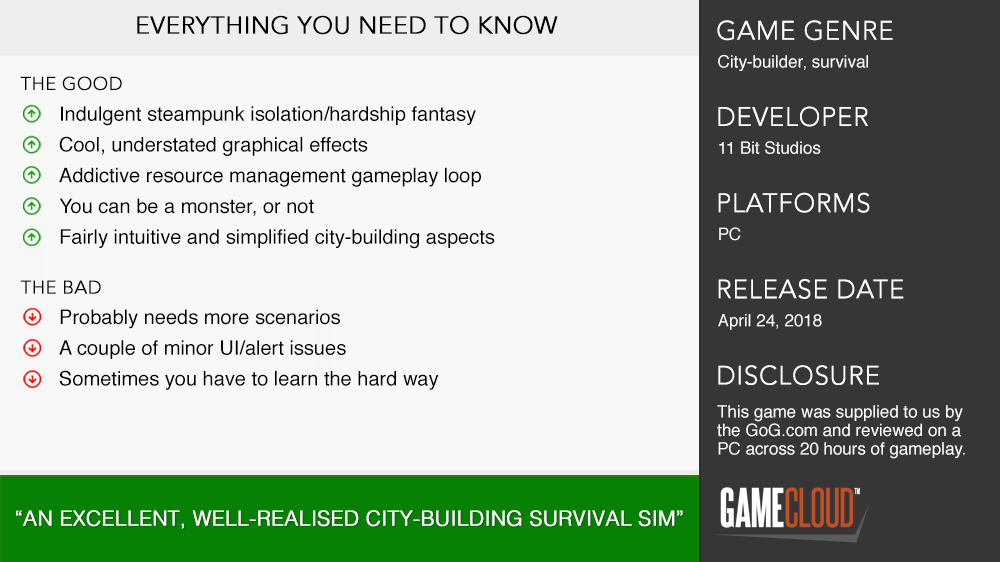

Survival games have been all up in the mid-list zeitgeist of late, as have games set in places of debilitating cold. It is perhaps outside the scope of this review to speculate why these things seem to strike such a chord here in the year 2018. Nevertheless, Frostpunk’s existence has a kind of inevitability about it. That it should be released a couple of months after Surviving Mars, The Long Dark, Subnautica, Northgard – to name a moderately popular handful – moulds it as peculiarly prescient. Forget for a moment Frostpunk’s decent gestation time and release date setbacks – it couldn’t be a more “now” game unless it had a Battle Royale mode or was a turn-based game about mechs fighting each other. Is there such thing as free will? I offer Frostpunk up as evidence that there is not – which is not to take away from the creative efforts of diviners/deliverers of this software, 11-Bit Studios, the mid-sized Polish studio who also made well-regarded survival game This War Is Mine.

Frostpunk is, I should clarify, a city-builder survival game (itself an emergent hybrid sub-genre that seems particularly of the moment). It’s set in an alternative 1880s. An unceasing global winter has devastated the earth, and you lead a group of refugees from Victorian England who set up a colony in the far north (for some reason) around a giant coal heat-generator. Fortunately, you’re surrounded by near-infinite supplies of coal to burn, and wood and iron with which to build everything. Also, your steampunkyness will eventually let you research aesthetically pleasing balloon-flying technologies and also develop giant spindly automatons to do the work for you, as indicated unsubtly by the title. (An alternative tagline I just came up with on my own: “Use steam to survive the frost, punk!” No worries 11 Bit, you can ETF me directly for that one).

A big part of Frostpunk’s appeal for me is endemic to its premise, which is that you are looking after an isolated community in a dire wintry situation. A sense of home and community-building is implicit, as is the potent notion of a flame of humanity holding steadfast against the elements. It’s an indulgent fantasy that basically sells itself, but it would be remiss not to point out all the nice touches that bring it to life. Between the arc of the sun and the shifting shadows around your camp, the ever-changing direction of the wind, the warm glow of fires against the white and grey surrounds, the weather effects slowly ramping up as you fall deeper into your snowpocalypse, and the subdued dramatic text that augments each story, your Frostpunk home is compellingly realised both as a bastion under siege from the weather and a last-hope home for your people.

Said people move about in what seems, for a sim-game, a satisfying pace. In the course of a day they’ll leave their dwelling, go to their workplace, go to the Cookhouse for something to eat, maybe go to the pub or church before heading back home to bed (unless you’re making them work overtime, or there’s building to be done, or maybe if they’re part of the hunting group that goes out each night in which case, heck, they aren’t getting out of bed ’til 4PM anyway). That you can watch each citizen’s highlighted avatar go about their complete daily life is a small thing that after a while you’ll probably stop noticing, but I felt deeply appreciative that this system existed, as it gave some weight to the idea of individual lives within the colony.

In saying that, I’ll also recognise that it’s the flip-side of this scenario which will be more interesting for a lot of players: you’re playing as a ruler in a dire situation, and you will need to make tough choices to beat the odds. You can become an absolute tyrant – either through the means of religious enforcement or plain old fascist law and order. The moods of your citizens are collectively measured on two meters: one for Hope, which you want to increase, and one for Discontent, which you want to minimise. If they get too mournful about their chances of survival, or unhappy with how you’re ruling, you might fail. Frostpunk offers routes to small dictatorship as ways to mitigate these problems, the idea I guess being that if the people aren’t happy about things on their own, you can make laws to trick or force them into being happy (or at least, pretending to be happy). Just like real fascism, woohoo!

I think it’s just as important that you don’t have to go down those routes, or at least, the main incentives for doing so (outside of morbid curiosity) are usually a desperate necessity for when things are rapidly falling apart. But if your game is going okay, you might not feel the need to declare yourself God-King and have an inquisition hit-squad to beat up non-believers. And that’s a good thing. The ways the game treats these moral quandaries are ponderous too. For instance, after choosing on my first attempt not to sign a law putting the children of New London into the workplace, everything subsequently fell apart much later due to a lack of total available labour in the end-game. So I signed it as soon as it became available on my go, which caused a small amount of discontent at first, but after a while both I and my subjects became inured to it. Consequently, I always had enough available labour to stay on top of things, and my second run seemed almost too comfortable (nor did I have to resort to signing other more draconian laws).

Frostpunk bases its core loop around a complex web of resource management, which is driven ever onwards by the plummeting temperatures in which your colony finds itself. So for example, you need coal to power your generator, and over time you’ll need to be collecting coal at a higher rate than you burn it. As it gets colder, you’ll burn more coal, and thus need ways of collecting it faster. To get more coal, you’ll need to build more and better mines, which will require lots of wood and steel, which you’ll also need to collect. What you do you mean you aren’t getting them fast enough? Well, you’ll have to do lots of building and upgrading there too. In some regards, it feels almost more like an RTS than a traditional city-builder, with the player racing the game clock rather than opponents to get suitably efficient production systems in place.

At the same time as trying to up your heating capacity for the future, you’re also trying to balance the needs of the present. You’ve also got to manage the health of your citizens and keep them fed. You’ll also want to send scouts out into the hinterland to explore and collect extra resources, which becomes its own map-based text adventure. These scouts are not to be confused with the hunters, who automatically leave the colony to hunt for food every night. Oh, and if your citizens are exposed to colder conditions they can become sick, in which case they’ll need to treatment from medical facilities (but the more preventative thing is to try and stop them from getting cold in the first place). At every moment there’s always one more thing that needs doing, and so I found myself playing it for hours on end without really noticing my evenings slip away.

While the resource-management side is intricate and complicated, colony infrastructure is a relatively straightforward concern. You don’t have to worry about the usual city-builder problems of sewerage, for instance, or water supplies, or electricity. Instead, you connect everything up via “road,” which means drawing lines on the vertices of the grid without requiring you to set aside extra space. Moreover, the details of how you do this don’t matter so long as ultimately the thread connects to the central generator.

Building placement is slightly more tricky, considering the differing shapes and varying insulation properties and operational heat requirements of different buildings. You put structures on a circular grid that whorls out from the central generator, so you end up with something visually akin to an emperor penguin colony huddling together in a protected circle. At the beginning of the game, only the immediate ring around the generator receives its heat, but you can upgrade its range as you go – the timing of which will inevitably be another concern to juggle. You’ll also be able to build mini generators which act as satellite heat sources, although these can end up burning through a lot of extra coal (as I found out the hard way), so you’ll still need to be intelligent about where you put them.

I’ve quite enjoyed most aspects of the frozen steampunk fantasy, the essential resource-management loop and the plodding construction of quaint circular settlements. One potential downside at the moment, though, is that you can only play Frostpunk (as it stands) in a scenario/story-driven way. So while I found the events of the first scenario challenging, surprising and captivating the first time, it was much easier to plan and build my colony correctly/efficiently to beat the arc of the challenge on my second playthrough. I think this is a problem, in that the game works best when it’s keeping the player on their toes and forcing them to adapt, but it necessarily struggles to do this again once the player’s already seen the events of the scenario.

Other issues are minimal. I found the road-building tool a little bit buggy, in that I’d often have to paint over the same lines a couple of times to complete the connection. Also while the game has an elegant panel UI, finding and clicking on the desired building in your city becomes difficult owing to the repeating shapes and snowy exteriors, especially later in the game when the weather escalates and the colony sprawls out. Similarly, I sometimes had problems finding events that the game was trying to alert me to. It uses a prominent thudding audio cue to signal things that might need your attention, like a particular bit of unrest in the city, or that your law book has finished its cool-down period, or that the scouts had reached wherever you’d sent them and needed further instructions. I’d often hear it and spend a long time searching on the screen for what it was telling me, sometimes not finding anything, while at other times missing important notifications for longer stretches than ideal.

I think perhaps it also doesn’t do a great job of teaching the player about things that become necessary in the late game, and I think in some ways I had to fail once to learn a few things that the game hadn’t explicitly told me. This may not necessarily be considered a bad thing (especially as events in Frostpunk are story-driven and unfair in a way you might not expect from traditional city-builders anyway), but each run can take several hours, so time-strapped players might find this aspect frustrating.

For the most part, Frostpunk is exactly what I hoped it would be, and more besides. It’s an aesthetically realised addictive management game, and it cleverly pulls in disparate gameplay elements to craft a feeling of isolated, desperate warmth against the crippling cold. I like it a lot. It also provides avenues for tyranny, if that’s your thing. Its main issue at the moment is a slight lack of content, as its three scenarios suffer a bit in terms of replay value, but given the devs have already committed to future (hopefully unpaid) extra content, I’m hopeful this won’t remain a problem for long.