For as much as I love the survival horror genre, there has always been one prominent game series that has eluded me: Fatal Frame. It’s a franchise that I’ve forever been meaning to try, and yet, for one reason or another, have just never found an opportunity to play despite there being five mainline instalments and a 3DS spin-off. Funnily enough, I even bought a Nintendo Wii just so I could play Fatal Frame: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse and Silent Hill Shattered Memories. Luckily the latter turned out to be excellent too, because, as irony would have it, Fatal Frame IV never ended up being released outside Japan; much to my dismay. Having missed out despite good intentions, I swore that I would play the sequel announced for Wii U (Maiden of Black Water); especially given the potential of the gamepad. However, as irony would have it yet again, I was booked out with other reviews and forced to skip past it. I needed to put an end to this.

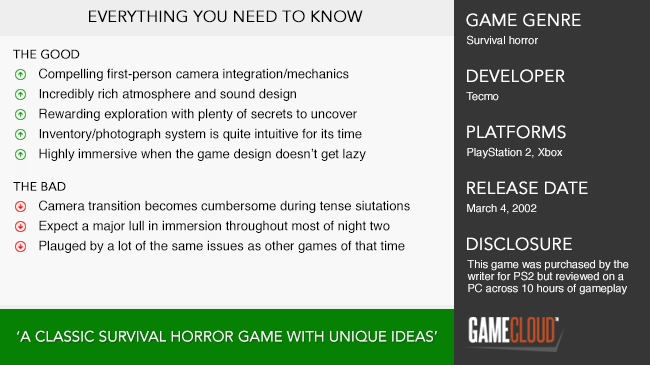

After careful consideration, I decided that it would be far more beneficial for me to go back to where the series began. Not only am I very nostalgic for that era of Japanese survival horror (arguably its prime), it was also around the time where fixed camera angles were still very popular, but the genre had moved away from those dreadful talk controls popularised by Resident Evil. Don’t get me wrong, there were still some mild annoyances to contend with, but with the ability to emulate the game on PC (having purchased the original first, of course), I was confident I could work around some of those issues, and was more than keen to give it a try. First released in Western territories on March 4, 2002 for PlayStation 2, Fatal Frame (AKA Project Zero) was an original game from creator Makoto Shibata and published by Tecmo. Strangely, though, the Western release was branded as being based on a true story, which is a bit of a stretch.

Set in the year 1986, the story of Fatal Frame follows siblings Miku and Mafuyu Hinasaki and their encounter with the haunted Himuro Mansion. What’s odd is that the game opens with the brother, Mafuyu, arriving at Himuro Mansion in search of a famous novelist who went missing while investigating its dark history. It’s not explained why, and you only play as Mafuyu for the prologue chapter (which is entirely in black and white), before he goes missing himself. It’s not until after this point the game opens up; when you take on the role of his sister, Miku, who arrives shortly after to find him. While playing, there are three distinct storylines to unravel; each being set in a different time period. As to what’s based on truth, though; according to urban legend, there is a Himuro Mansion located somewhere outside Tokyo city, and the game’s concept is said to be based on Shibata’s own spiritual experiences, but there are no certifiable events.

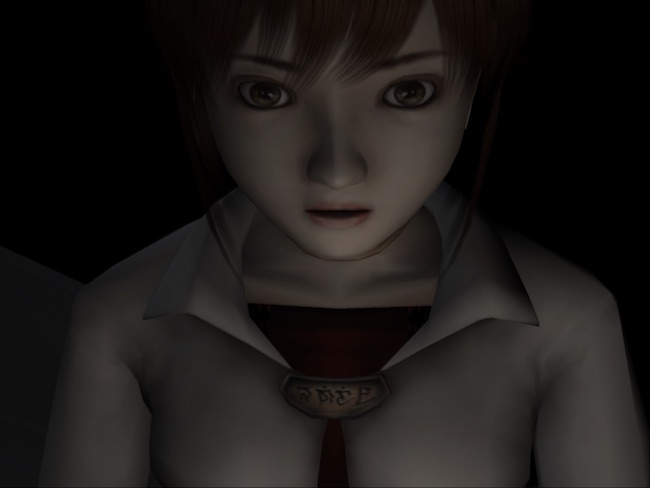

At a glance, Fatal Frame shares a lot in common with the original Resident Evil, in that it’s set in a mysterious mansion where you must survive with limited resources, solve puzzles, and collect items. However, thematically speaking, it’s much more akin to Japanese horror films such as Ringu (1998). If I’m being totally honest, though, a lot of the game’s components are quite standard for the genre at that time, with one exception: the Camera Obscura. You see, Fatal Frame doesn’t rely on conventional violence like with most survival horror titles; instead, hostile enemies can only be fought using an antique camera that has the ability to capture ghosts. Much like most early ’00s survival horror, you’ll experience the game from a third-person perspective. However, when looking through the camera, the game switches to a first-person viewpoint. This was quite revolutionary for its time, even if it is clunky to control by today’s standards.

While combat is an important component of the gameplay, the camera also plays an intricate role during exploration too. Miku is gifted with a “sixth sense” that allows her to track spiritual activity within the environment (represented by a HUD indicator that glows blue or orange depending on what’s close by). Not every encounter is hostile either, which means taking photos is a big part of what makes Fatal Frame so unique and rich in atmosphere. For example, the on-screen indicator will glow blue if there is a secret hidden nearby, and it’s this constant engagement that helps to keep players immersed in the environment at all times. In addition, every photo you take earns points, which can then used to upgrade the camera’s special abilities and combat proficiency. All the photos you take are stored in your inventory, which is a neat feature in itself, but also quite useful as you can review them to know who exactly you’ve encountered.

On the first night of the game, I was surprised by how quickly I was able to immerse myself. Learning how to use the camera obscura was was a lot of fun despite the awkward controls, and initially exploring the mansion left me feeling unnerved a lot of the time because resources are in short supply and you don’t yet know what to expect. The sound design in Fatal Frame is truly excellent, so much that it easily overshadows the outdated visuals and atrocious voice acting. Despite a lot of common tropes such as solving puzzles to unlock doors and collecting journals and audio logs to fill in narrative gaps, the atmosphere in the Himuro Mansion is so rich that it’s easy to look past the game’s weaker points early on. Once you reach the second night, however, things take a bit of lazy turn. Your map resets, you have to explore the mansion all over again, and, by this point, you know what to expect, so it’s mostly pointless backtracking.

As I was emulating the game, however, it added the ability to speed up the gameplay and quick save/load whenever I found myself in a dead end. This helped to alleviate the lull, as, by this point, all of the ghosts had become familiar and just served as a mild hindrance. Sure, there are a few new areas and secrets to uncover, but it wasn’t scary anymore, and that was disappointing. Fortunately, things took a stronger turn in nights three and four. After allowing players to get overly comfortable, the difficulty level increases significantly, and this once again forces you to scrape for resources and even run away from some encounters as they are not worth the risk or wasting film on. It was at this point I found the game most compelling. At its core, the story isn’t anything you haven’t seen in J-horror before, so while it serves its purpose, without tense gameplay and meaningful exploration, the game starts to feel wooden and a bit predictable.

Despite the fact it’s not actually based on a true story, Fatal Frame stands out as a classic survival horror game due to its unique ideas, strong sound design, and fantastic atmosphere. So much I believe it can hold its own against genre juggernauts such as Resident Evil and Silent Hill. That said, I’d be remised to not mention the incident where the rights holders for Ghostbusters tried to sue Tecmo because the game involved “capturing ghosts” with a camera… No joke. In hindsight, there are a number of small issues I could pick at, but most are simply a product of that era; for example, clunky combat and terrible voice acting. If anything, the biggest issues it faces are lazy design and a predictable story, and that leaves me bright-eyed and eager to check out the sequel. If you’re bored of zombies and the recent flood of mediocre indie horror games, I’d recommend Fatal Frame. It’s perfect if you like ghosts and want to get a bit nostalgic.