Game Name: Pridefest

Developer: Atari

Interview with: Fred Chesnais, Todd Shallbetter, Tony Chien, Matt Labunka, Mark Perloff

Current version: Pre-alpha

Intended Release Date: Q1 2016

Genre: Social Simulation

Intended release platform: Android & iOS

Editor’s Note: Due to technical issues on Atari’s end, the interview was unable to be recorded and later transcribed here. The description of the interview as it happened has been recounted from notes taken by Patrick Waring and the PR representative of Atari. The questions at the end of the article are email questions sent to Atari as a follow-up after the interview, and have not been altered prior to publishing.

Towards the end of last year, I was invited to speak with Atari CEO Fred Chesnais about their upcoming mobile title Pridefest, a game, “designed to unite members of the LGBT community.” LGBTQ representation in gaming is a topic I’ve looked at recently and was very interested to see how one of the most well-known companies in the industry would handle the issue. Not well, as it turns out. Pridefest’s premise is built upon several troubling stereotypes, layered over the top of your usual mobile freemium fare, with a social network attached on the side. While I’m sure the game was meant as a tongue-in-cheek way of interacting with the LGBTQ community, the whole thing is just vaguely offensive.

And rather pushy on the social media side of things.

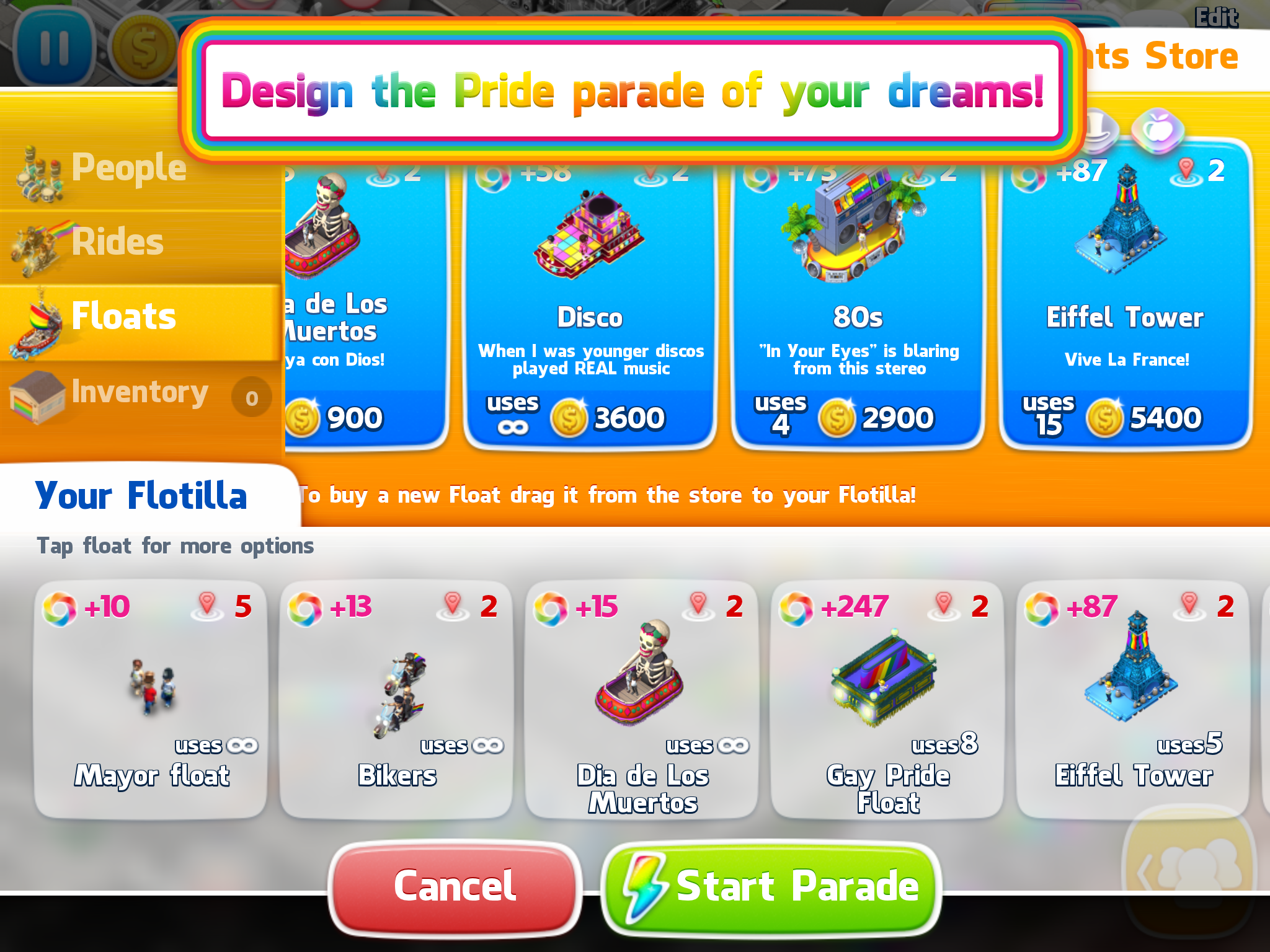

I imagine Pridefest as the kind of game your homophobic uncle would design if he were trying to be inclusive around Mardi Gras. Your character is inaugurated as the mayor of a town that’s super glum, so much so that all the buildings are drab grey to show how sad they all are. To perk everyone back up, it’s your job to run constant (and I do mean constant) pride parades through your city, passing by as many buildings as possible to spread your happiness. The grey buildings can then be torn down and rebuilt as living areas or businesses that contribute resources, which allow you to purchase more floats and attractions to run more pride parades.

I’m not just being sarcastic about the buildings being sad, either. Buildings in Pridefest are a representation of your town’s mood and attitude, literally displaying a frowny face when they’re unhappy with things. The grey buildings that you’re tearing down all appear to be decent sized apartment complexes or office buildings for the most part and are often replaced with small houses or boutique businesses. If the game were going to be completely light hearted and avoid any serious issues at all that would be one thing but you’ll also encounter protesters during your parade runs. This is worth mentioning because when you run into a group or protesters, both they and one of your floats will disappear after a sudden and dull “thud” sound effect.

Ponder that for a moment.

The gameplay itself isn’t much better, since if you strip away the narrative you’re left with fairly basic freemium app-store trash. The same short piece of music loops incessantly in all areas of the game until you hear echoes of it in your sleep. That is until a pride parade starts, which is an actual assault on your ears. The wait times without paying real money to speed things up are totally obscene, and I say this as a regular player of Boom Beach. Even as far as free to play games go, there’s precious little in the way of actual content in this title. The social networking aspect is, I suppose, where the bulk of the application’s interaction lies. I can’t imagine why people would want to use it, however, when Facebook can provide just as much homophobia without having to play a sub-par game at the same time.

I honestly don’t know who this game was made to appeal to because it certainly isn’t the LGBTQ community as a whole. It’s as though after picking their target audience they thought about all the ways they could make said audience feel uncomfortable and then turned that list into a game. I showed it around to more than a few people, some of my queer friends included, and couldn’t find a soul among them who thought this was a good idea, let alone entertaining. If this was meant to be a game made in jest, it’s the kind of jest you’d expect from an early 90’s radio DJ when it was still okay to say “poof” on the air. Needless to say, my impression of the game was rather dim and I went into the interview expecting something of an awkward conversation.

Even in a game about the LGBTQ community, the number of rainbows in this game just feels excessive.

Though it had initially been the arrangement to speak only with Fred, four other senior members of Atari’s team joined us for the interview. The team were very keen to express their interest in making games for and about the LGBTQ community. “It’s something I’ve wanted to do for awhile,” Fred explained, “we wanted to create something new.” Todd Shallbetter, current COO for Atari, elaborated further, “this is something we at Atari have wanted to do for a while, especially leveraging the Pridefest brand.” It felt like there was a lot of love for the LGBTQ community, and a shared desire to see a game made that connects with queer players, but not a lot of explanation as to why.

Todd went on to add, “from a strategic perspective, it certainly makes sense to launch a game for an under-represented community.” This strategic element is, effectively, the driving force behind Pridefest. It goes a long way towards explaining why Atari have made a game for the LGBTQ community without considering how its content might appear to their target audience. Of course, I asked if they were at all concerned about how the game might appear to audiences and I was assured by Tony Chien, Senior Director of Marketing, that this was something they’d considered. “We’ve thought about that,” Tony countered. “Pride fests are established events that happen across the world as a celebration of inclusivity, so we feel that the game is in line with that.”

“It’s something I’ve wanted to do for awhile… we wanted to create something new.”

Tony explained that the development team at Atari consulted with many queer devs and players though skillfully avoided answering if any LGBTQ developers worked directly on Pridefest. Throughout the interview, the word “fun” had been dropped at least a couple of dozen times and making things entertaining seemed paradoxically important to them, given what they’d created. I broached the question of why this was so important and Tony stepped up once again to answer. “We saw, and we know, that it’s an under-represented community in the gaming industry… We’ve always been a pioneer of reaching new video game audiences; this is just another example of that.” Todd, helpfully, provided a much clearer answer:

“It’s good to be on the right side of history. We believe this cause is being embraced by the world, and the tide has turned for equality. That is why it’s important for us.”

The interview ended not long after, with a few details being exchanged regarding the game’s release, and I was later informed of the technical difficulties with the interview recording. Following the interview, I was offered a chance to follow up with some email questions about the game:

Pridefest’s description says the game is “designed to unite members of the LGBT community,” and during the interview Tony said this would translate to “invite friends, create pride, and celebrate diversity. Doing this with others is a way to push that message forward.” Can you tell us what this game’s message is and how this player interaction helps to push that forward?

Fundamentally, Pridefest’s message is simple: there should be safe and inclusive platforms within the gaming community for all people to have fun and express themselves. Aside from the core of Pridefest gameplay, we’ve designed the game to include in-chat and club functionality so players – regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity – can meet and interact socially. Pride is only a small slice of the LGBTQ experience, but it’s one centered on fun, freedom of expression, and joy. Pridefest represents the spirit of LGBTQ equality, and we wanted players of the game to feel that spirit manifest in gameplay and by interacting with each other.

“It’s good to be on the right side of history. We believe this cause is being embraced by the world, and the tide has turned for equality. That is why it’s important for us.”

During the interview, in response to “Why is creating a fun and welcoming atmosphere in the game important to you?” Todd responded with “It’s good to be on the right side of history.” What does this mean for the game, exactly?

While the media has increasingly embraced opportunities to portray aspects of gay life in film or art, it remains an underserved community – universally and in the gaming industry. However, certain games or characters in games have broken through; I think of indies like Gone Home, or the potential for same-sex relationships in BioWare and Bethesda games – but there really aren’t many titles that directly focus on aspects of LGBTQ life, especially in the mobile space. Atari is synonymous with the video game industry, and producing a game like Pridefest further moves the needle towards a greater acceptance of the viability of games geared toward LGBTQ audiences. That is meaningful to us.

The character dialogue and narrative text in Pridefest is all centered around the parades, which is good for a central mechanic but makes for very one dimensional characters and comes across as very stereotypical. Given that this is meant to be a celebration of the LGBTQ community, are there plans to expand the interactions with the town to better represent the LGBTQ community’s interests and issues?

The game is fundamentally about running Pride Parades. As such, the majority of the interaction within the game is going to be centered around that. It is obviously impossible to make a game – or any piece art – that can successfully encompass the thoughts and opinions of an entire community, especially one as variegated and unique as the LGBTQ community. What Atari wanted to do was highlight one small slice of LGBTQ life: the Pride Parade. While rooted deeply in protest and social justice, the Pride Parade is a celebration above all else. We’ve been privileged to experience that universal spirit of joy at events like GaymerX, FlameCon and NYC Pride. This is what we wanted to share. Elements like freedom, pride, color, acceptance, celebration…all made Pride the ideal core feature in making Pridefest.

Prior to its worldwide release, we launched Pridefest in test markets Canada, Australia and New Zealand because we expected and wanted feedback. We recognize this is a topic fraught with the potential for stereotyping and pandering, and it’s the last thing we would ever want to do. We are extremely sensitive to how this game comes off generally and most importantly to our core audience. (Full disclosure: the version currently available in our test markets features some initial placeholder language that was unfortunately not swapped out. We have done a re-write of much of the copy in the game, which will be implemented shortly.)

“Our development team and Atari worked in concert with an advisory board of figures within the LGBTQ gaming community.”

Were there any LGBTQ developers involved with the development of Pridefest?

Our development team and Atari worked in concert with an advisory board of figures within the LGBTQ gaming community. Their input has been invaluable in ensuring that we’re making not only a fun game, but one that respects the community we are catering to and designing the game for.

Regarding the question I had about the speed of the game’s progression, Matt responded with “We will put a game out, see the reviews, but a lot of the game happens behind the scene. A lot of that comes from a lot of people on the title.” Can this be elaborated on, and how adjustments will be made over time?

Atari is committed to listening to user feedback and adjusting gameplay and features. Part of the reason for the rollout in select countries before our worldwide release is to gather input on what parts of the game people respond to, what isn’t working, and what can be improved upon. As seen in our other mobile titles, we roll out consistent and frequent updates addressing in-game issues as they arise, along with proactively improving the game through our own internal processes.

Given the slow progression of the game, and the current level of gameplay content in comparison to other free to play titles, are there plans to add to the gameplay mechanics? Perhaps something that ties in with the social media functions of the game?

We are constantly ideating on potential new features to increase the longevity and re-playability of the title. The “story” mode and attached missions were introduced recently, and adds significant value to the player’s in-game experience. We are certainly looking to build-out some of the challenges into missions or projects beyond simply designing and running Pride Parades. As an example, we have certain missions tied to decorating a part of your city in a specific way, according to theme. As production continues on the title, we will have much more to show!

“While the media has increasingly embraced opportunities to portray aspects of gay life in film or art, it remains an underserved community – universally and in the gaming industry.”

I personally cannot recommend this game on any level, and, following my interview with the Atari team behind it, the entire thing makes me feel uneasy. Take from this interview what you will, however, in the opinion of this writer, the motivation behind Pridefest’s development is cynically exploitative at best and predatory at worst. Given Atari’s renewed corporate focus over the last few years, its difficult to see this game as being anything else. There should be more games that represent the LGBTQ community at large, their interests, and simply the fact that they’re just regular people; that’s just not something that this game does.