One of the first things I did in Super Lucky’s Tale was swipe a group of frogs off a cliff. I came across them after having just learned in quick tutorial style what Lucky the fox was capable of in the jumping and spinning department, and these frogs were just there, hopping around at the start of the first level. I gave them a good ol’ flick of the tail to see what would happen, and off they went into the impermeable void. This was surprising because I’d learned just minutes before that Lucky would pass through the many NPCs who had anything to say to you, so someone had gone to the trouble of making these tiny ornamental animals murderable. Not only that, they seemed to have no other purpose whatsoever. The game made no comment upon my actions, but then neither did they respawn until Lucky himself went to his first of many deaths not long after.

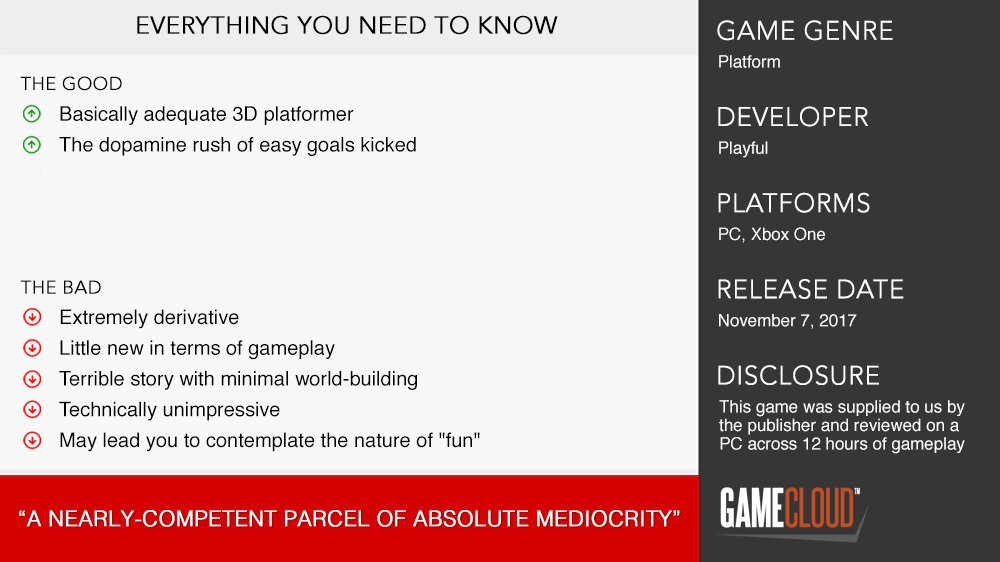

Now, the fact that you can murder harmless animals isn’t at all an important gameplay element of Super Lucky’s Tale, which is an otherwise unremarkably suitable-for-children 3D platformer. I do, however, think it’s emblematic of some deeper problems as to how Playful Corp went about building this game, which is largely devoid of a personality while being full of strange inconsistencies that almost, from a certain angle, add up to one. I also largely mention it because this incongruous ability to be quietly cruel is one of the only things that sets Lucky apart from any other 3D platformer to have come before it. It is otherwise woefully, fanatically, almost incredibly derivative.

Take the protagonist, for example, who is such a perfect rip-off of existing tropes that you might swear you’ve seen Lucky before. Perhaps he was a second-tier Diddy Kong Racing character (he looks particularly similar to Conker the squirrel), or maybe he’s a hardly-seen cousin of Sonic that Microsoft accidentally won the rights to during a drunken bet at E3. Of course, he is neither. Lucky is a new IP (this is his second appearance after last year’s Oculus title, “Lucky’s Tale”) whose immediate familiarity is simultaneously impressive and nauseating.

Elsewhere, Super Lucky’s Tale picks idea liberally from its forebears. Aside from the Rare-esque aesthetic, Lucky collects coins (hello Mario) as well as the scattered letters of his name (hi, Donkey Kong). My partner took one look at the visual design and asked me if I was playing Croc, and music in the second world seemed lifted from the theme of Conker’s Bad Fur Day. 3D platform adventures do tend to repeat ideas, and you could argue there’s little point in swapping items out when functionally you’ve got the same product, but here Super Lucky’s Tale oversteps the tributary line. I’ve seen it described as “a love letter to platform games”, but these references come over as lazy and unfulfilled, as though it’s a home-brand version of the games you actually remember and like.

It seems like the game was built to emulate the experiences of older platform titles in a shorter space, and it has a condensed feeling. Rather than sticking with and exploring the possibilities within a style to create variety, it goes for a smorgasbord approach from platforming history, throwing in more than a few 2D side-scrolling levels and a couple of endless runner stages along with the more regular 3D worlds. As a result, it doesn’t do any of them particularly well. Lucky has a small skillset, and if you’re looking to see 3D platforming explore new territory, this isn’t the place for it. There are ninety-nine clovers (your main progression trophy) to collect. The levels all have a linear structure, with one main clover set as the finish line and three others (one from collecting 300 coins, one from the five letters that spell Lucky, and one you’ll need to complete an unspecified mini-objective for somewhere along the path). This means that while you might easily grab four clovers in one go, going back to get the ones you’ve missed can be a chore as you always have to complete the main objective clover again – read: redo the whole level – in order to make it count. This compact, linear structure also reduces these levels to, well, levels in a game, rather than imaginative, dynamic spaces that reward curiosity and remain memorable after the fact.

Perhaps this would be okay if the game had bothered investing in a narrative, but Super Lucky’s Tale seems particularly starved in this department. Lucky, you, fox, are a (buzz word of the moment) “Guardian.” We never see any of Lucky’s world as, in a particularly unnecessary framing device, the game begins with Lucky getting trapped inside a magical book – the Book of Ages – along with his enemies, who quickly take over the world (of the book). Clearly Lucky must therefore save all the inhabitants (of the book) and defeat his foes, who are, by the way, all cats. (*It’s probably an accidental parable, but as it is with invasive pest species in Australian ecosystems, here too must the cruel apex-predator fox act as a control mechanism on the mesopredator cat – both are invasive and disastrous to native species, but arguably left to its own devices the cat is even worse). Lucky travels through four different thematic chapters (sky castle, farm, desert and haunted), each overseen by a different one of General Jinx’s archetypal underlings (the ninja one, the technological one, the army one, the fashion-oriented one). At the end of each world when you beat the boss the Book of Ages reappears and opens. This is weird because you’re already supposedly inside this very book, so Lucky jumps into it in what visually suggests “book-ception,” but narrative-wise just indicates you have access to the next world now.

It might have helped if each of the four worlds didn’t seem so isolated from each other, or if more NPCs who reappeared over the course of the game, or anything at all to build the world up a bit and make it seem like more than a series of barely thought-through excuses. It’s also a weird thing in that stories never seemed that important in your Marios etc. I mean, It’s not as if Lucky’s predecessors have had mind-boggling or profoundly affecting narratives, but at least they’ve created spaces that you could see as more than just a framework for item-collecting, which often here is all I’m inclined to see. And without a substantial game world to fall back on, it’s just that much more apparent how unoriginal and safe the gameplay is, which is where you start asking what the point is.

Perhaps you could argue that there’s a place for games that just want to repackage and resize the experiences of older titles for newer audiences, but then even from a mechanical standpoint, Super Lucky’s Tale is far from smooth. From the first deaths caused by shonky camera perspectives through to its incredibly tedious final boss, it regularly requires forgiveness. It shrugs the same jagged edges that were part-and-parcel of 3D platformers back in their heyday, along with some unwelcome new ones. Why, for example, must it take me to a loading screen every time I alt-tab back into it? Why must a game with blessedly little in the way of visual clutter have frequent frame-rate problems? Why are there all these bits of level confusingly sitting in plain sight that we can’t get to, not to mention all these invisible walls? Why is the supposedly rotatable floating camera continually confined to, like, thirty degrees, so I can only ever view the level from one direction? Is it still 1998? Has anyone heard about Y2K?

The thing is, moment to moment, actually playing Super Lucky’s Tale is okay. It’s mechanically adequate and visually pleasant enough that I could finish it without feeling like I had to force myself. Moving Lucky across platforms and bopping enemies with his small repertoire of double jump, burrow and tail-spin, feels fine and easy – not great mind you, but not broken. The music is mostly inoffensive; the art is clean, simple and inviting. The NPCs are innocuous and forgettable, while the setups for objectives are your borderline absurd fare worth the occasional stifled laugh. Between the bright colours and the condensed design, it’s strangely easy to get caught up in it, to lose twenty minutes here and there as coins and clovers accrue with little thought or effort, which, for some, might be enough criteria ticked to be a successful game. Whether or not it’s rewarding to engage with is another matter entirely, though, and there’s a joyless emptiness at the heart of the game that remains once you’ve put the controller down.

The problem comes when you stop to ask yourself: why play this? It isn’t for the nostalgia of a favourite genre, as here Super Lucky’s Tale ends up in uncanny valley territory. It isn’t for fun, inventive, different or compelling gameplay, which is lacking. It isn’t for the challenge, of which there is little beyond what’s caused by perspective and structural problems, and it certainly isn’t for the narrative, world-building, or for being able to flick tiny animals over the edge of the world, all of which the less is said, the better. All that remains is the short, dully addictive achievement cycle provided by the rapid collect-a-thon, a system (and subsequent feeling) which, when you get down to it, rings all too similar to the endless, transient spool of notification bubbles from your social network of choice.

In the end, it’s difficult to see the point of Super Lucky’s Tale from either a commercial or critical point of view. If you (or your children) haven’t played the games that Super Lucky’s Tale bowerbirds, there’s no compelling reason to not be playing those instead (beyond, perhaps, their availability on Xbox and PC). If you have, there’s hardly enough here to justify your time, money, or emotional integrity. At best, it’s a sugary, adequate if frequently flawed distraction. At worst, it’s a morose void belching an existential crisis, poorly concealing the frantic absurdity of all existence beneath its irreverent cartoon veneer.