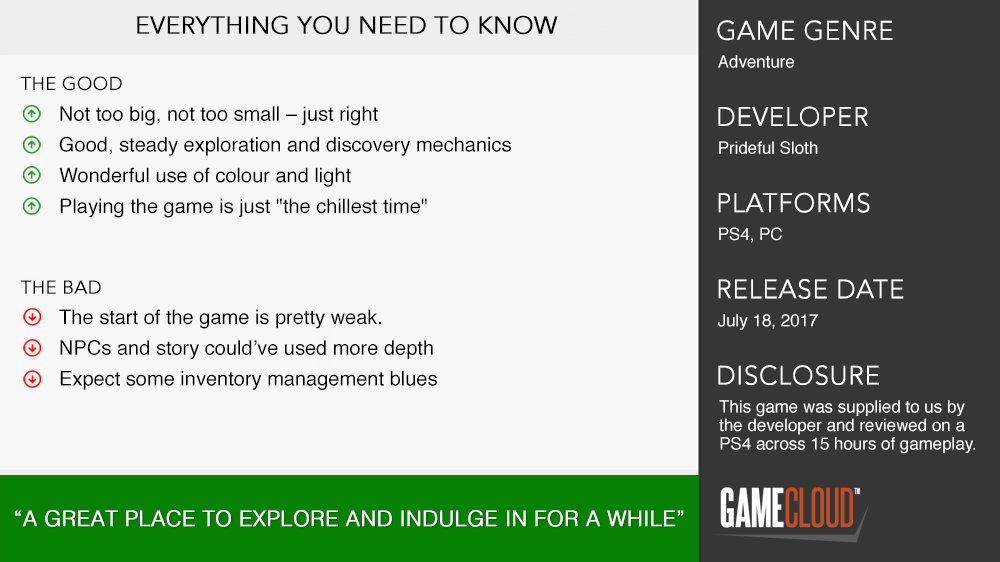

Yonder: The Cloud Catcher Chronicles is a whimsical open-world adventure game. It has no combat and no puzzles; instead, progress comes purely from exploration and by finding, trading and crafting items. It was developed by Prideful Sloth, a self-described “micro-AAA” studio started by some industry veterans in Brisbane. I didn’t know any of this when I started with it, and for a while I kind of hated it. However, gradually, without realising it, my feelings changed, and now that I’m done, it’s one of my favourite games of the year.

You begin your journey on a boat headed to the mystical island of Gemea, which, as the game informs you, is where you were born, but your parents sent you away when you were very young. The place is still functioning but has become mildly sick, you see, and is covered in patches of purple cloud known as “the Murk.” On your way lightning strikes and you end up shipwrecked at a cave-mouth on the island which is where you begin your journey proper. It turns out – because you are the protagonist in a video game and so you must be special – you can see these “sprites” that inhabit inanimate objects, making you, indeed, the “sprite-seer.” Sprites live all over Gemea. Other people know that they’re there, but they can’t see them. However, because you can see them and talk with them, you can take them with you and harness their power to clean up the Murk and restore Gemea to its former glory.

Initially, the game directs you towards a village to find help. Everyone there seems to know that you’re a person who was shipwrecked, no big deal, but no one wants to welcome you properly or anything. Instead, they just get you to pick up sticks for them. Then one of them shows you how to transform those sticks into something greater – a bundle of sticks. “Oh no. It’s a crafting game,” I wrote in my notes with a sinking heart. An entire game focussed on my least favourite aspect of many other contemporary RPGs. I almost wanted to give up then and there.

It wasn’t just that, though. The days turned into nights alarmingly quickly, which was making me feel weirdly stressed. You get to build farms, but it’s too much effort to do much with them. Nearly every NPC I ran into seemed available to work for me as a farm hand – like, are none of these people occupied already? None of them had anything interesting to say or showed much potential for conflict or character development. Some of them seemed to like terrible puns. Mostly, they felt like a flimsy, transparent means to an end. A lot of them seemed to be the same character model as someone you’d met in the previous location, just with say, a different colour beard. “This is Stardew Valley meets Zelda by way of Tellytubby Land,” I wrote in my notes. For some reason that made sense at the time.

It wasn’t long before ran into inventory management blues. This is the eventual state of every game that requires collecting a lot of items you might need without knowing exactly what’s going to be useful later on, and it’s something I suffer from frequently in any game like this. You have a perennially full backpack, which makes life is difficult, so you have to work out what to sell off at any given moment. Furthermore, Yonder has a fairly unique currency system in that it doesn’t have one. It’s back-to-basics bartering for you. You can trade items; each of which has a value that fluctuates depending on what the location has and wants, for other items that the trader has in stock. It’s quite refreshing and easy in some ways, but it does force you to make difficult decisions at times, especially when you’re trying to keep the right things on hand to complete several different quests at once.

Of course, even a game where collecting is the primary activity must still have a pointless map collectable. In Yonder’s case, this role is filled by actual cats. These rotund blobs meow to alert you to their presence if you’re nearby, from boulders, in corners, from behind veils of Murk that you can’t wash away because you haven’t yet found enough sprites. It’s a point of genius, and I can’t believe this is the first time I’ve come across it. Eventually, these mewling kitties are given a contextualising quest (spoiler: an old lady lost all her cats), but even without it, you have to wonder why no other game has done this first. Think how much it would have improved, say, any Assassin’s Creed title had they asked you to look for cats rather than some of the other pointless trinkets they invented.

What’s interesting is that at some point – perhaps during the first winter, as snow was falling around the fields, or maybe as I stumbled into a festival village snuggled away in a glacier on Gemea’s frozen coast – I realised that I was really enjoying myself. Where Yonder succeeds – where it utterly succeeds, in a way that I didn’t notice until I was several hours deep in its trap – is in capturing a rolling, quiet sense of discovery and possibility. It turns out Gemea is a really nice place to explore. The game is both big enough to comfortably fit in several different climates while being small enough to get across on foot. There are different biomes, each with a different weird animal or two, as well as different plants, textures and colours. The map also belies how many different routes there are, as well as secret passages, claustrophobic tunnels, and nooks in the hillsides. All the different villages are beautiful, artfully decorated, and homely in their own way, even if the characters within them aren’t exactly compelling.

I came to appreciate how Yonder Chronicles subtly encourages you to explore. It doesn’t shout at you: “OKAY NOW GO FIND THIS PLACE.” Rather, you’ll realise there are things you need but don’t have yet, and there are bits of the map or parts of your book that aren’t uncovered yet, so maybe you should just walk in that direction and have a look around. So you do, and you’ll find something new and cool. Inevitably, not all pathways are available at first – sometimes they’re blocked by Murk, sometimes you need to come back later with the right materials to build a bridge, or occasionally you’ll just not notice a passage winding through the rocks.

It’s all very calming, too. Like, once you get over the quick day/night cycles and put the inevitable inventory management stresses aside, it’s nice to wander around and perform simple tasks for people, within the very straightforward framework that the game sets up. The modicum of flexibility in how you play means you can largely avoid the farming or crafting side of things – to a certain extent. Perhaps most notably (and it took me a long time to realise this was the case) there really is no combat whatsoever. There’s no killing of monsters big or small nor the slaying of bosses. Sure, you carry around such dangerous items as an axe, a pickaxe, a giant mallet – but you use these to wreak destruction on inanimate objects such as boulders or barrels, or the hapless landscape itself. It’s weird that this “no combat” thing should make such a difference to the mood of a place, but it really does. Your progress also doesn’t rely on brain-teasing puzzles – most of the tasks you do in the game require item collection and exploration. Nothing more, nothing less. And as there’s no time limit, you can just come back once you’ve got a hold of whatever ingredients for whatever the person or thing needs, if you happen to be in the area, or, you know, whatever. Yonder Chronicles doesn’t really care and neither should you.

One thing that can’t be denied is that Yonder Chronicles is a beautiful game, and in a way that’s more than the sum of its cel-shaded polygons and Unity engine. I’m personally really taken with the use of colour and lighting. As time shifts, and as you move around the map, accidentally stumbling on natural, practical, un-signposted vistas, you get a great sense of this world and can come to believe in it, and in a way that the story and NPCs can’t quite do on their own here. You really feel the seasonal cycles, and you can even forgive the fast days and nights, as they bring so many immense dusks and dawns. At night, everything beyond your lamp light gets blotted into grayscale. It’s all very subtly restrained and impressive.

Yonder: The Cloud Catcher Chronicles is a game that wears its limitations and shortcomings on its sleeves. It has many things about it that I don’t particularly like and yet it is also somehow very worthwhile. It provides a really nice place to explore and indulge in for a while. It’s also just the chillest time – a phrase I wouldn’t use lightly nor willingly, not without wincing, but Yonder Chronicles kind of demands it. It’ll probably make a pretty good detour from whatever is bothering you in life right now. It did for me.