It’s not uncommon now days for independent game developers to look to the past for inspiration. In truth, overall development costs are a lot cheaper with this approach, and it’s also a good way to capitalise on all of our nostalgia fueled memories. With that being said, though, as a result, it’s become increasingly difficult to pick out the genuinely good games from all the cheap cash-ins. For this reason, I feel particularly inspired to write about a Swedish-developed, ’90s styled, adventure game called “The Samaritan Paradox.” If you haven’t heard of it, don’t worry. If you’re a fan of the genre, I am confident that you will want to check it out by the time you finish reading.

The year is 1984, and Ord Saloman is an aspiring cryptologist living in Gothenburg, Sweden. He’s supposed to be writing for his Ph.D., but currently lacks the motivation to put pen to paper, oh, and not to mention the fact that he’s also two weeks behind in his rent, as well. In an attempt to get himself thinking outside the box, Ord decides to read something a little unconventional, a book titled: “The Last Secret” by Jonaton Bergwall; written by a local author who had recently committed suicide. While reading, however, Ord uncovers a hidden message intended for Jonaton’s daughter, which simply reads: “there’s one more.” Immediately, he contacts Sara Bergwall, who hires him to pursue the truth. She suspects there is another book, but for reasons unknown, is unwilling to pursue the matter herself. Did her father commit really suicide? What is this book about? It’s up to you to uncover the truth.

It’s been a long time since I played a point and click adventure, in the conventional sense. In fact, I think Broken Sword II: The Smoking Mirror was the last comparable title I had completed prior to today, to be completely honest. It’s not because I didn’t enjoy the genre, but because I more so gravitated towards a console experience when I was younger, and by the time I got another PC, the genre was not nearly as prominent in the industry as it once had been. With that being said, though, this made my time with The Samaritan Paradox that much more special. In many ways, it was like stepping back into my childhood, however, because the game explores themes which are clearly adult, and more appropriate to my interests now; it felt like an entirely new experience, as well.

Recently, at an event held in Perth called The Game Changers, I got an opportunity to hear from several well-known video game writers. One guest in particular, Clint Hocking, who is best known for his work on Splinter Cell and Far Cry 2, made a surprising comment about how he really wants to see new ways to explore themes in games other than through violence. With this in mind, it’s hard to deny that game design struggles to function without some form of violence to drive the gameplay; albeit, with a few exceptions from time to time. As a fan of narrative in games, I couldn’t agree more, and while the design in The Samaritan Paradox is nothing new, I found such joy in the exploration of themes that just wouldn’t work the same in any conventional style of game today.

The premise of following clues to locate Jonaton Bergwall’s last book sounds simple enough. However, as is common with this style of narrative, the plot quickly develops into a multi-threaded investigation, with Ord pursuing several other local conspiracies, as well. In turn, I never found myself growing bored as I had various leads to pursue at any given time, and I have to admit, it was refreshing to find myself caught up in a story that wasn’t driven by conventional means. This isn’t a grand tale about someone trying to save the world, and as such, you shouldn’t expect to see James Bond-styled villains, or death defying acts of heroism. This is a game that’s reasonably grounded in reality, filled with seemingly regular people, and I think that’s what I liked most about it.

With that being said, though, the player is also given the opportunity to play out the sub-narrative of Jonaton’s book (one chapter, at a time), which does add a unique fantasy element, to an otherwise serious investigation. In reality, the events in this story are meant to be a metaphorical representation of Jonaton’s ultimate secret. However, despite the intent, it does still feel as if you’re stepping into an adventure like Kings Quest, with a ship-wrecked woman suffering from amnesia; who must, in turn, defeat a dragon in a battle of wits, among other obstacles to find her way home. These were some of my favourite moments, for which I personally felt contrasted well against Ord’s real-world pursuits, and in turn, kept me anxious to discover what it was actually trying to say.

The gameplay mechanics of The Samaritan Paradox will feel familiar to anyone who’s played a point-and-click adventure game before; either recently, or more than 20 years ago. As is expected, players will spend their time clicking around the environment, collecting items, and thinking of clever ways to use them. It might not sound very exciting on paper, but it’s more so meant to serve as a means to an end; relying on the quality of the writing as to whether it works well or not. Most of all, though, this is a puzzle game, and one which refuses to hold the player’s hand. In my opinion, this is where the design truly shines, as there is a consistent variety in the way players are challenged: whether with clues, riddles, or literal puzzles which must be solved in order to progress forward. If you’re someone who feels that adventure games have grown predictable, you will not be disappointed.

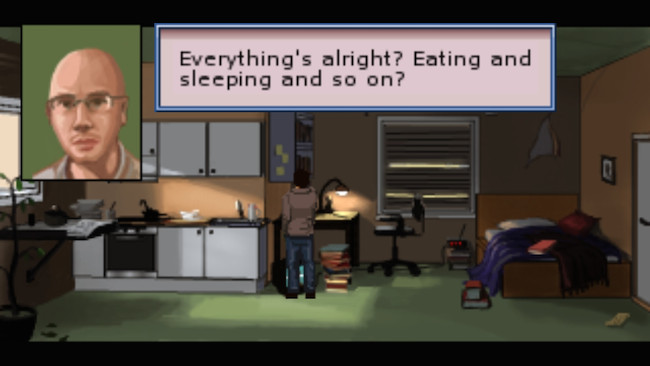

As you would have quickly noticed, the game is presented exactly as it would have been 20 years ago; right down to the resolution, which is 320 pixels wide. Everything about this game is meant as a homage to adventure games from the early ’90s, albeit with the hindsight to avoid common design problems from that era. For me personally, this was a strong part of games charm, and it felt appropriate given the period of the narrative, as well. I didn’t feel as if this was a case of using nostalgia as a cheap trick. I’d also like to recognise the soundtrack, which was composed by Lannie Neely; best known for his work on To the Moon and Social Caterpillar. It almost always fits the tone and era of the game perfectly. If you’re a fan of video game music, I’d recommend picking it up, as well.

The Samaritan Paradox is a paragon example for interactive fiction that doesn’t rely on violence or sensationalism to tell a compelling story. It achieves exactly what it sets out to do by paying homage to all the great adventure games of old and does so without feeling like a cheap imitation. In fact, had this game been released in the early ’90s, I genuinely believe it would have been critically acclaimed for its strong themes and unique approach. The writing is multi-threaded, with a superb blend of noir and fantasy, and it is driven by puzzles that you can expect to get stumped on along the way. Most importantly, though, with any mystery, the participant should expect to be shocked by the conclusion, and this is one area the game will definitely not disappoint. If you’re someone who thinks modern adventure games have become too easy, or someone who just never got around to playing any of the greats from that era, The Samaritan Paradox will definitely be for you.